image: thrifty_swag

image: thrifty_swag

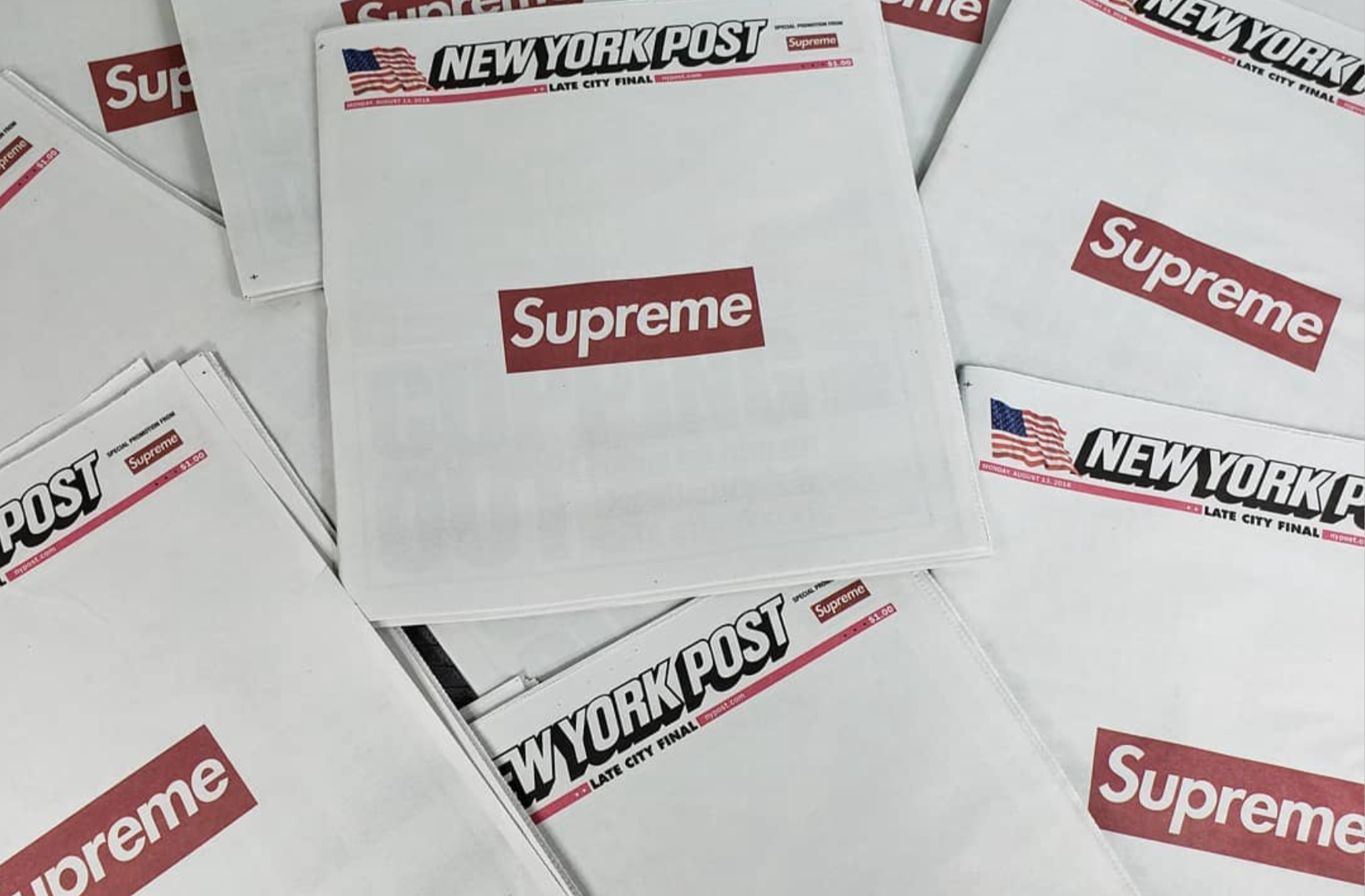

On Monday morning, the New York Post was sold out in many locations across the city by about 7am. “The rush on The Post after a relatively quiet August weekend had nothing to do with the news,” wrote the New York Times’ Jonah Bromwich. Instead, it had “everything to do with” the front page of the daily New York paper, which was devoid of almost all of its usual staples. News-related imagery were nowhere to be found. Headlines had been banished. In their place was, instead, the paper’s header and Supreme’s bold box logo.

According to the Times, the cult streetwear brand – which first opened its doors on Lafayette Street in April 1994 and has since spawned a following that high fashion brands, such as Louis Vuitton, are desperately attempting to replicate – “approached The Post in late April asking for ‘original, never-before-seen, creative ideas.’ The newspaper’s 5-year-old in-house creative strategy agency, Post Studios, proposed the wraparound” advertisement. Four months later, the paper hit newsstands and both fans, and the internet, were abuzz.

The release of the special issue predictably sent Supreme fans into a frenzy, just like how its partnership with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority last year – which resulted in a limited run of Supreme-branded subway cards – did. In fact, this level of fury is hardly a novel phenomenon for Supreme; each week when the brand “drops” new products, whether it be limited edition screen-printed t-shirts, branded bricks (yes, actual bricks emblazoned with the Supreme logo), or collaborations with the likes of Nike, Rimowa, or Levi’s, dedicated consumers diligently line up at the various Supreme stores for access. Security guards stand at the doors, as if Supreme were De Beers.

What might be the most interesting aspect of Supreme’s latest endeavor is the timing of it: The New York Post ad placement comes just days after Vanity Fair’s latest issue hit newsstands. The cover of the Condé Nast-owned magazine – which stars actress and Louis Vuitton brand ambassador Michelle Williams wearing garments from Louis Vuitton’s Fall/Winter 2018 collection, photographed by Collier Schorr, who also shot Louis Vuitton’s latest ad campaign – caught the attention of critics, namely, the New York Times’ Vanessa Friedman.

Given the magazine’s choice of cover star and her contractual status as a Louis Vuitton ambassador, its decision to style her in wares from the brand’s F/W 2018 collection (the $1,440 woolblend pullover and $2,590 lambskin miniskirt that Williams wears on the September issue cover are currently available for purchase on Louis Vuitton’s website and in stores), and it commissioning of an LV-approved lens-woman, it is “hard not to wonder, if the cover is effectively … a Louis Vuitton ad,” Friedman asserted in an article last week.

A spokesman for Louis Vuitton called the cover specs “a happy coincidence,” while a representative for Vanity Fair said the magazine chose Ms. Schorr to shoot the cover in May, before it knew that she was behind the Louis Vuitton ad campaign. Meanwhile, Friedman suggested that the eery commonality is “a sign of the times.” After all, she noted, “Magazines have long blurred the line between commerce and editorial content,” just never quite so blatantly.

The Vanity Fair cover is hardly the first potential ad campaign in disguise. It has long been the deal that brand ambassadors appear on magazine covers in the brand they are paid to represent. That is why Selena Gomez was photographed for covers in Louis Vuitton for awhile and more recently in Coach; the same can be said of Alicia Vikander, a Louis Vuitton ambassador, and Jennifer Lawrence, who is formally tied to Dior – just to name a few.

Similarly, magazines have been known to buddy-up to big brands that pay for advertising. In an interview last year, former British Vogue director Lucinda Chambers spoke to Vogue’s preferential treatment of advertisers, saying, “The June [2017] cover with Alexa Chung in a stupid Michael Kors T-shirt is crap. He’s a big advertiser so I knew why I had to do it.” A few years before that, an internal Harper’s Bazaar document – which listed the brands to feature in upcoming editorial spreads, ranked according to priority, and helpfully divided them between “Advertisers” and “Non-Advertisers” – made the rounds online.

In recent years, a bolder iteration of this pay-for-play practice has come to the forefront – the additional element of the brand-specific photographer, thereby creating some kind of brand-controlled triad. You may recall last year when Bella Hadid covered Vogue Arabia’s September issue. The “it” model – who was, at the time, the face of Fendi – was dressed head-to-toe for the cover and accompanying editorial in Fendi’s Fall/Winter 2017 collection, while Fendi creative head Karl Lagerfeld served as the photographer.

And in an even more explicit nature, BoF reported last fall that magazines have been “turning their front covers into ads. As far back as 2014 major publishing companies from Time Inc to Hearst Magazines have been experimenting with cover advertisements.”

These fashion covers seem to have quite a bit in common with Monday’s New York Post cover, in that they are essentially ad campaigns. But there is one important, distinguishing factor: Aside from the “New York Post” logo at the top of the paper’s front page, as well as the usual $1 price tag and the date, there was a notation in the top right corner that reads: “Special Promotion From Supreme.”

In other words, the front and back covers of the Post are an ad for Supreme, which sold something like a 50 percent stake of its brand to private equity giant the Carlyle Group for $500 million dollars last fall. More than merely an ad, though, the Supreme cover-as-advertisement play is one that speaks pretty perfectly to the status quo of publishing, particularly in fashion, where covers are readily up for grabs for brands that have the cash.

It seems fitting that some iteration of that disclosure language should routinely accompany the growing number of magazine covers, which are increasingly borne from big checks and which are masquerading as independent editorial – as opposed to advertorial – content, but that is almost never the case. Against this landscape, the Supreme x New York Post manages to capture the entire zeitgeist in one fell swoop.