Amongst the Bangladesh-made t-shirts, Turkey-produced linen tops, printed shorts from Indonesia, and crepe cotton skirts produced in China on H&M’s website are “Made in Ethiopia” wares. The retail giant is among some of the world’s largest and most well-known apparel brands, including Levi’s, Guess and PVH-owned Calvin Klein, that rely on suppliers in the African nation, which is proving a popular manufacturing locale as garment manufacturing costs are extremely low, thanks, in large part to a large pool of apparel laborers, who are some of the “lowest paid in the world.”

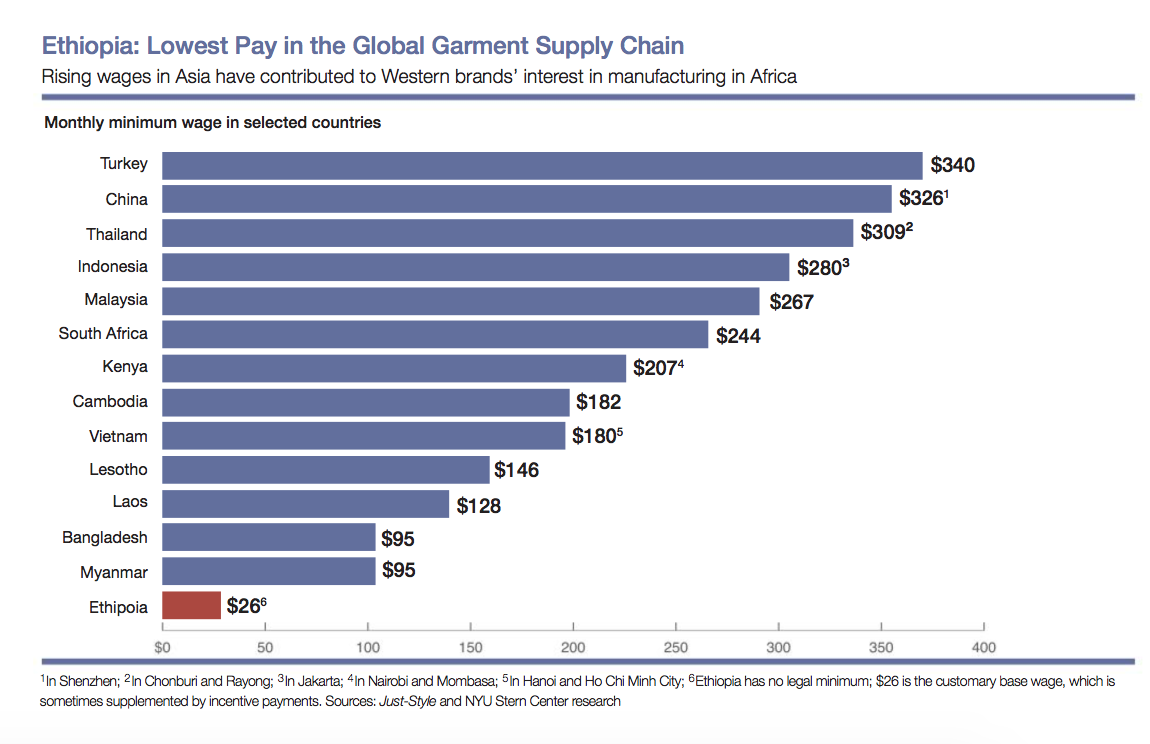

According to a recently-released report from New York University Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, individuals involved in Ethiopia’s burgeoning garment manufacturing sector receive an average of the equivalent of $26 per month. Based on that amount, “Workers, mostly young women from poor farming families, cannot afford decent housing, food, and transportation,” the report’s author Paul M. Barrett and Dr. Dorothee Baunmann-Pauly,assert.

And even when factory operators “provide additional modest payments for regular attendance and meals, workers struggle to get by.”

The government of the county – which boasts a population of 105 million and one of the fastest growing economies in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund – has been actively courting global attention to and investment in its garment manufacturing sector, particularly in recent years, as “labor, raw material and tax costs have risen in China, the world’s dominant textiles producer,” per Reuters.

As a result of ever-rising costs in China, countries such as Myanmar, Bangladesh and Vietnam emerged as popular options for the market’s price-conscious brands, such as fast fashion retailers and other mass-market entities. In response to the large-scale movement out of China to such lower-cost manufacturing centers, countries, such as Ethiopia, have “scrambled to offer an even cheaper alternative, and go up against the newly-established low-cost garment makers like those in Bangladesh and Vietnam.”

While Ethiopia’s $145 million in annual garment exports are situated well below its $839 million in coffee exports, $424 million in oilseeds, and $229 million in flowers, the nation’s government has “identified apparel as an industry” in which it can thrive based on the success of “a number of other poor countries that have entered the sector [and had success] because of strong global demand for inexpensive clothes,” according to the report.

Just like other similarly-situated nations, Ethiopia’s government, which does not observe a private sector minimum wage, has been tempted by “the relatively modest cost of setting up garment factories, and the abundance of low-skilled jobs” that such an industry creates, which is particularly striking as about 50 percent of women in Ethiopia are unemployed, according to the NYU report.

As such, the government has been busy “positioning Ethiopia up the rungs of the global textile supply chain,” with the hopes of boosting its $145 million industry into one that is worth $30 billion. Barrett and Baunmann-Pauly note that “the path for workers will not be smooth.”