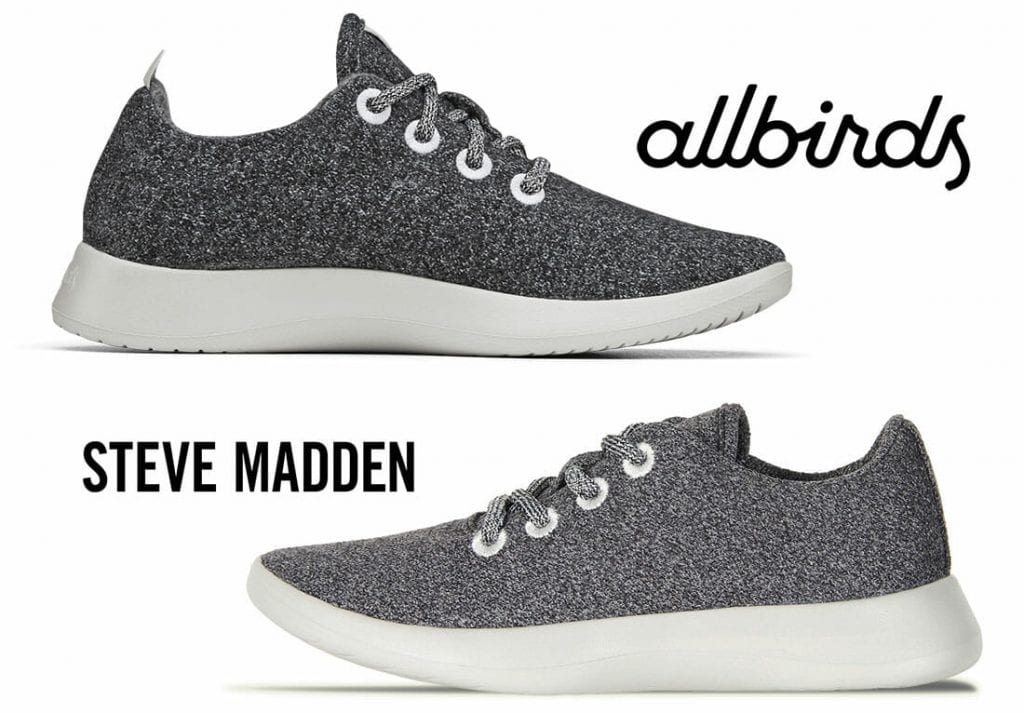

Steve Madden, himself, may be toying with the idea of retiring but his eponymous label’s penchant for copying is in full force, according to a new lawsuit filed by fellow footwear brand Allbirds. According to San Francisco-based Allbirds’ complaint, which was filed in federal court in San Francisco this week, Madden is on the hook for allegedly copying its wool trainer, giving rise to its claim of trade dress infringement.

As first reported by BoF, Allbirds – which was officially launched in 2016 by Tim Brown, a former New Zealand soccer player, and Joey Zwillinger, a bio-engineer – boasts just two styles of footwear, including its Wool Runner. The brand describes its staple sneaker as “a remarkable shoe that’s soft, lightweight, breathable, and fits your every move,” and alleges that last month, Madden began selling its own lookalike version, the “Traveler” sneaker for $89 by way of its own site, as well at Macy’s and Zappos.

What has not been discussed yet: Whether Allbirds has a case.

The foremost question in determining whether Allbirds could actually claim a victory in the case, if it were to go to trial (which it likely will not, since Steve Madden tends to settle most cases brought against it, and there have been many, including ones from Dr. Martens, Balenciaga, and Balenciaga, again, Valentino, there was Aquazzura, and Stella McCartney, and the list goes on), is whether or not Allbirds’ Wool Runner sneaker can boast trade dress protection in the first place. In short: Do consumers associate the Wool Runner design with the Allbirds brand?

For the uninitiated, trade dress protection extends to “the total image of a product,” and it “may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics or even particular sales techniques.” As a type of trademark, the critical element of trade dress is the ability of the configuration – i.e., the design and shape – of a product itself, to serve as an indicator of source for consumers.

So, in much the same way as the Nike “swoosh” logo enables a consumer to know a product was made by Nike, the design and shape – or trade dress – of a Birkin bag automatically tells a consumer that the bag is made by Hermes. The same goes for the red sole of Louboutin’s shoes, which is also protected by trade dress law.

In order for a design to be eligible for trade dress protection, just as how the Birkin bag is, it must have “secondary meaning” – aka the average buyer would associate the design with a single source – and proving this, which is what Allbirds would have to do, is not necessarily an easy task.

Typically, to prove that a design has secondary meaning, a party will need to present evidence in the form of direct consumer testimony, consumer surveys, and/or documentation of circumstances, such as the length of time the design has been used exclusively by the manufacturer, the type of advertising, advertising expenditures, the number of sales and customers, and any proof of intentional copying.

As you can see, this is a high bar for most brands, and would almost certainly be a tough fight for a brand that, like Allbirds, has only been on the market for a year or so.

And it is worth noting that even if Allbirds was to establish that its sneakers merit trade dress protection, it would then have to show that consumers are likely to be confused as to the source of Madden’s footwear in connection with its own.

What we will almost certainly never know is if Allbirds could make such a case on either front. The pattern in most cases, intellectual property infringement ones, included, is that the parties settle their differences out of court and long before it is time for trial. Nonetheless, the real thing, Allbirds’ Wool Runner – which sees the company partnering with one of the world’s great Italian textile mills to create “an innovative wool fabric made specifically for footwear, and successfully designed the most comfortable shoe imaginable” – seems pretty cool and far more worthy of shopping than Madden’s cheap copy.

UPDATED (Feb. 7, 2018): Madden has counterclaimed that Allbird’s asserted trade dress “is generic, lacks secondary meaning, and is merely ornamental” and “consists exclusively of functional elements.” Madden’s defense relies on Allbird’s own statements that its design is simplistic as well as third-party use of similar designs.

* The case is Allbirds, Inc. v. Steve Madden, Ltd., 3:17-cv-07067 (N.D.Cal.)