image: Unsplash

“I feel robbed,” says Cecilia Keil, who has had her designs copied en masse by international retail giants. None of them “know the significance and the meaning of the prints,” which are derived from Samoa’s cultural art prints and “that belong to our people,” Keil notes. Aside from being disappointed that her work has been “duplicated” without her authorization, the Samoan fashion designer says there are “ethical complications around bigger clothing apparel companies profiting off the intellectual and cultural property of Samoa.”

Keil is not the only artisan speaking out. In fact, she is part of a growing group of international craftsmen tired of having their regionally-distinctive creations land on the runway or in the stores of global retail chains.

Simply being credited as “the inspiration” behind high fashion’s seasonal offerings and fast fashion’s unending supply of garments – oftentimes after the fact – provides them little reward. Many groups want to see tangible benefits, such as paychecks and/or the opportunity to collaborate, when their work is translated, often line-for-line, by brands – which have ranged from Isabel Marant and Louis Vuitton to Urban Outfitters and Mango – for their own financial gain.

This is something that Keil and individuals from an array of different regions in the world are speaking out about in light of consistent and widespread misappropriation. The residents of Tenango de Doria – a small town located in central-eastern Mexico that boasts a community that is famous for the intricately stitched and brilliantly-colored tapestries that have been a product of theirs for many generations – have been forced to join the discussion in the recent past.

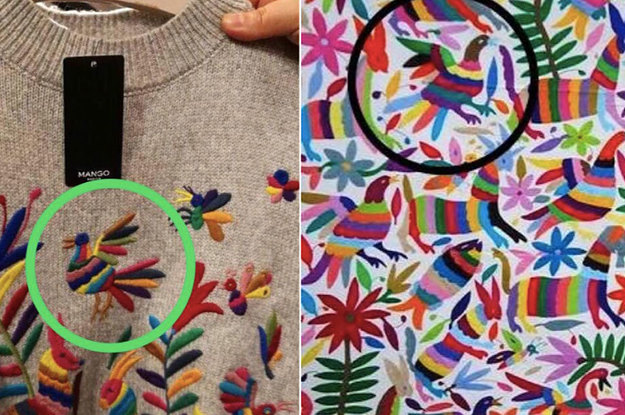

After having their work serve as the subject of inspiration or target of imitation (depending on who you ask) by the likes of a handful of fashion brands, including Paris-based design house Hermes, Mexican brand Pineda Covalín, and as recently as this past October, Spanish fast fashion giant Mango, the artisans of the region are speaking out.

image: Mango’s sweater (left) & a Tenango de Doria design (right)

Ezequiel Vecente, a craftsman living in Tenango, told Al Jazeera’s John Holman, “We can make anything, but we should be paid a fair amount. That way we can get ahead, generate employment here, and pay people fairly.”

In a similar instance, “Last summer Madewell copied a traditional blouse made by artisans from Chiapas, Mexico,” says Harper Poe, the founder of Proud Mary, a fashion venture that partners with global artisans. “I had been talking to [Madewell] about doing a collaboration. They knew I had contacts to this group [of artisans],” and would have loved to have given these artisans the opportunity to make these blouses for Madewell.” No such collab ever came into fruition, says Poe, as Madewell simply “copied” the design.

Part of the problem in many cases is that many of these artisans’ designs are not protected and even if they are, the communities often lack the recourses necessary to weather an international legal battle.

Thanks to geographical indication rights – which “can provide the structure to affirm and protect the unique intellectual or socio-cultural property embodied in indigenous knowledge or traditional and artisanal skills that are valued forms of expression for a particular community” – artisans and manufacturers may be able to prevent unauthorized uses by third party.

Unfortunately for many artisans, these rights “are not easy to establish,” and come with “considerable costs, not just for organizational and institutional structures but also for ongoing operational costs such as marketing and legal enforcement.”

Such road blocks do not mean that artisans are not beginning to organize én mass to fight against the unauthorized usage of their traditional creations. After serving as “inspiration” from brands ranging from Diane von Furstenberg and Louis Vuitton to Land Rover, the Maasai have been working to prevent other brands from profiting at its expense. The Tanzania-based nation has looked to legal protections for the Maasai name and its indigenous prints, and as recently as this year, announced that they would begin taking action against those that use their intellectual property without their authorization.

Louis Vuitton (left) & Thakoon (right)

Kaqchikel Maya weavers in Guatemala are following in the footsteps of the Maasai. After spending years organizing and pushing for legal rights for their designs, the Kaqchikel Maya’s local municipality declared this summer that any traditional weavings and designs associated with town and the tribe are part of the heritage of the Kaqchikel town. As a result, any action by third parties to use these designs requires consultation with the weavers – most of which have organized with the Women’s Association for the Development of Sacatepéquez – prior to use.

As for the artisans of Tenango, they recognize that the fight for protection “is a daunting one,” but optimistic that their work with local government and cultural ministry representatives will hopefully cut down on the widespread piracy of their creations.

In light of such collective organizing, it is becoming increasingly risky, at least from a public relations standpoint, for brands to blatantly pluck regionally-distinctive designs from indigenous artisans. With that in mind, Poe says that “if you are going to try and replicate a certain aesthetic that belongs to an indigenous culture, bring these groups into your supply chain and create sustainable jobs.”