A group of plaintiffs has filed another amended complaint in their lawsuit against Shein, accusing the ultra-fast fashion giant of copying and selling their original designs without authorization and avoiding “blame” and liability for such “misconduct” by way of a “byzantine shell game of a corporate structure.” Aside from making claims under federal trademark and copyright law and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, the plaintiffs double-down on their allegations about the secretive AI-powered “algorithm” that has enabled Shein to scale from “small Chinese-based seller of bridal clothing … to the world’s largest fashion retailer with annual revenue approaching $30 billion.”

A Bit of Background: In the headline-making lawsuit that they filed in July 2023, independent designers Krista Perry, Larissa Martinez, and Jay Baron alleged that Shein and various related entities (collectively, “Shein”) are on the hook for copyright and trademark infringement in connection with their practice of “produc[ing], distribut[ing], and selling exact copies of their creative works,” which they allege is “part and parcel of Shein’s ‘design’ process and organizational DNA.”

At the same time, they asserted that Shein’s success can be tied to its use of a secretive algorithm that it couples with “a corporate structure, including production and fulfillment schemes, that are perfectly executed to grease the wheels of the algorithm, including its unsavory and illegal aspects.”

The Underlying Algorithm

While the plaintiffs wage a slew of allegations against Shein in their 74-page complaint, among the most compelling are those that focus on Shein’s algorithm. Despite “all of the public criticism of SHEIN,” including on the ESG front, the plaintiffs assert that “the story of its sheer technological success is underreported” – and the critical element, they claim, is the introduction and use of an algorithm that enables it to offer up a “rapidly changing assortment of trendy and remarkably affordable clothing, shoes, accessories, and beauty products.”

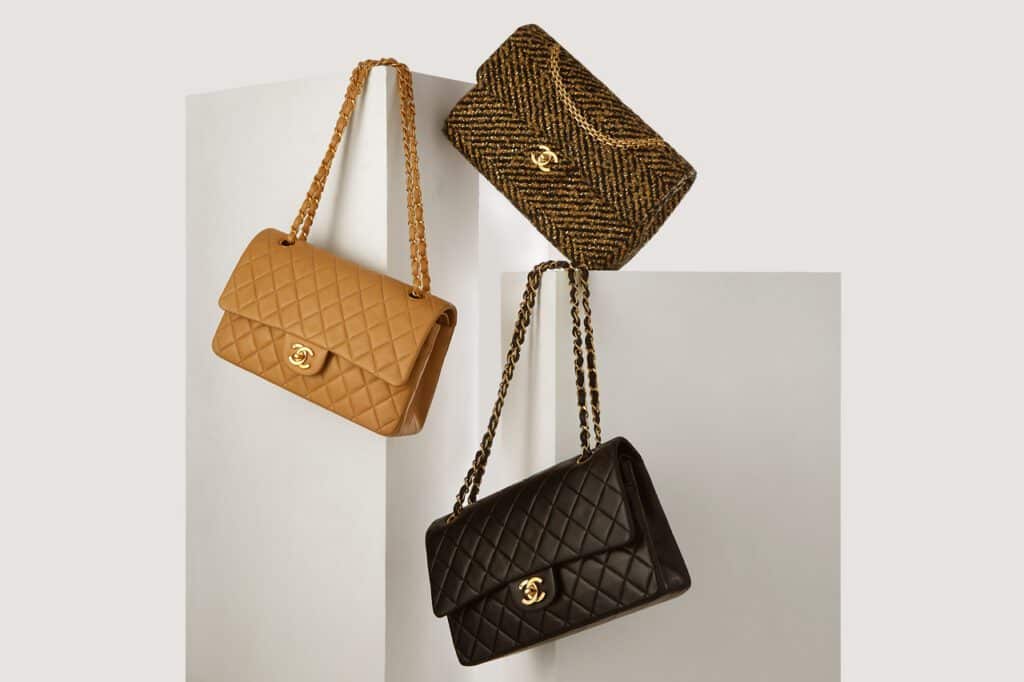

Echoing language from earlier filings, the plaintiffs assert that “there is no Coco Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent behind the SHEIN empire,” and instead, there is “a mysterious tech genius, Sky Xu (a/k/a Chris Xu), [who] made SHEIN the world’s top clothing company through high technology, not high design.” Specifically, they assert that Shein “has made billions [of dollars] by creating a secretive algorithm that astonishingly determines nascent fashion trends.”

Although the “details and precise methods” behind Shein’s algorithm are not publicly available, the plaintiffs argue that it “is possible to infer certain facts about [it] by looking at its results.” For example, they claim that it is “impossible not to notice that SHEIN’s process often generates products that are exact or close copies of the work of other designers: occasionally large ones, but more often than not independent leading designers, such as the plaintiffs.”

These designers are “just the sort who might be producing the most cutting-edge designs – and being able to identify them is the gold standard of a multi-million dollar trend forecasting company,” according to the plaintiffs, who allege that while “a new corporate apparel company can spend millions on trend forecasting firms, designers, and consultants … obviously, none has achieved anything close to SHEIN’s success.” In other words, Shein’s algorithm “has handily bested every human attempt to consistently design desirable clothing.”

As for the nature of the valuable algorithm, the plaintiffs assert in the lawsuit that Shein “purposeful[ly] creat[ed]” it, clarifying that “no one is suggesting that the algorithm developed itself to misappropriate the intellectual property of small designers.” Rather, the plaintiffs contend that Shein “built an algorithm purposefully designed to unearth and then misappropriate the most valuable asset an independent designer might have: commercially valuable designs.”

Without investigation, the plaintiffs claim that “it is impossible to describe the particulars of how the SHEIN algorithm produces its results – how a design for a blanket or overalls finds its way from a designer’s modest website to being cut and sewn in a sweatshop in Guangzhou, to then be offered for sale online (with millions of eager eyes waiting) for a price far below the original designer’s costs.”

Understanding the workings of the algorithm “requires unraveling SHEIN’s revolutionary business model, which is in some ways brilliant (as evidenced by the handful of new billionaires it has minted among its founders), but unfortunately also inherently causes some of the high-profile externalities … including systematic intellectual property theft,” the plaintiffs claim. However, what the plaintiffs say is clear now is that Shein knew that its algorithm “could not work without generating the kinds of exact or close copies that can greatly damage an independent designer’s career – especially because SHEIN’s artificial intelligence is smart enough to misappropriate the pieces with the greatest commercial potential.”

> Shein has sought to escape the lawsuit, arguing earlier this year that the plaintiffs fell short in alleging a civil RICO claim, as they failed to adequately plead willfulness to sustain criminal copyright infringement as a predicate act; to adequately plead mail and wire fraud as a predicate act; and to cure defects in their allegations of a RICO enterprise. The court sided with the plaintiffs with regard to their RICO claim last month, with Judge Mark Scarsi of the United States District Court for the Central District of California largely preserving the plaintiffs’ claims against Shein.

The case is Perry, et al., v. Shein Distribution Corp., et al., 2:23-cv-05551 (C.D. Cal.).