The European Commission has levied a 5.7 million euros ($6 million) fine on Pierre Cardin and its licensee Ahlers for breaching EU antitrust law by restricting cross-border sales of Pierre Cardin-licensed clothing. The announcement from the EU follows a probe into the French fashion brand and the German apparel company, which started in 2021 amid reports that the two companies had “developed a strategy to prevent parallel imports and sales to specific customer groups of Pierre Cardin-branded products by enforcing certain restrictions in the licensing agreements.”

The Commission previously stated that it had “concerns that the companies concerned” – which were subsequently revealed to be Cardin and Ahlers, a menswear manufacturer and Cardin’s largest licensee – “may have violated Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’) and Article 53 of the European Economic Area Agreement (‘EEA’), which prohibit cartels and other restrictive business practices.” The EU executive body initiated a formal investigation to assess whether Pierre Cardin and Ahlers have breached EU competition law by “restricting the ability of Pierre Cardin’s licensees to sell Pierre Cardin-licensed products cross-border, including offline and online, as well as to specific customer groups.”

The EU commission ultimately found that between 2008 and 2011 the two companies maintained anticompetitive agreements to shield Ahlers from competition in European countries where it held a Pierre Cardin license.

The penalty for Cardin and Ahlers is particularly noteworthy, as it comes amid an increasingly-focused-effort by the Commission, which has set its sights on the fashion/luxury arena. The agency notably targeted the fashion industry in 2021, probing the signatories of an open letter that called for “fundamental changes in the industry to make it more environmentally and socially sustainable,” including by adjusting the seasonal runway show and product delivery schedules in order “to encourage more full price sales” and fewer discounted wares in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

An interesting (although unsurprising) side effect of the widespread luxury brands price push and the overall fall of sales in the personal luxury goods market: A boom for resale. Earlier this month, we dove into the current limbo that the luxury goods market is facing (you can find that here), which is slated to see sales in the personal luxury goods market drop for the first time since the Great Recession. The status quo when it comes to luxury branded handbags: “Finding regular size [handbags] at less than $3,000 from reputed brands has become virtually impossible,” Luca Solca, luxury-goods analyst at Bernstein, told the WSJ.

The result is that many price-conscious consumers have pulled way back. Bain & Co. estimates that some 50 million consumers dropped out of the market this year “either because they can’t afford to shop, or they don’t want to because they don’t feel there is enough [creative] juice.”

Not all of those people have stopped shopping, of course, and instead, if the success of the likes of The RealReal, Vestiaire Collective, Vinted, and co. is any indication, many consumers are likely shifting their spending to pre-owned products. In an interview in WWD, French resale company Vestiaire’s CEO Max Bittner said that the company’s U.S. business “has accelerated significantly over the last six to 12 months.” The company does not report financial figures, but Bittner said that the company anticipates “revenue growth accelerating to north of 20 percent in the second half of this year” and noted that its gross merchandise value (“GMV”) (i.e., the value of the goods sold) is “around the $1 billion mark.”

Meanwhile, The RealReal’s sales and its stock price tell a compelling story. The San Francisco-based resale giant revealed early this month that its sales for Q3 rose 11 percent year-over-year to $148 million, prompting its stock to rise by nearly 75 percent since then. Its GMV for the 3-month period was $433 million (up 6 percent year-over-year) and expects its GMV for the year to fall somewhere between $1.810 and $1.826 billion.

And Vinted is fresh off a share sale that valued the resale company at 5 billion euros. The Berlin-based company says that it boasts more than 80 million members and saw revenues grow by 61 percent to 596 million euros in 2023, yet another nod to the appeal of the secondary market.

India is proving to be a hotbed for luxury brand expansion in recent years, with the likes of Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Valentino, Dior, Balenciaga, Rolex, Bottega Veneta, Cartier, and Bulgari, among others, setting up shop in Mumbai’s new JIO World Plaza; Chanel launching a country-specific e-commerce operation; and Dior staging its F/W 2023 runway show in Mumbai. Luxury goods purveyors have set their sights on India thanks to the expansion of India’s middle-income class and the steadily growing number of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals in the country.

In a nutshell …

> Bain & Co. puts India’s luxury market on track to expand to 3.5 times its current size (revenues for the Indian luxury goods market are expected to amount to $17.6 billion for 2024), reaching the $85 to $90 billion mark by 2030, nabbing India the title of the fastest-growing luxury market globally.

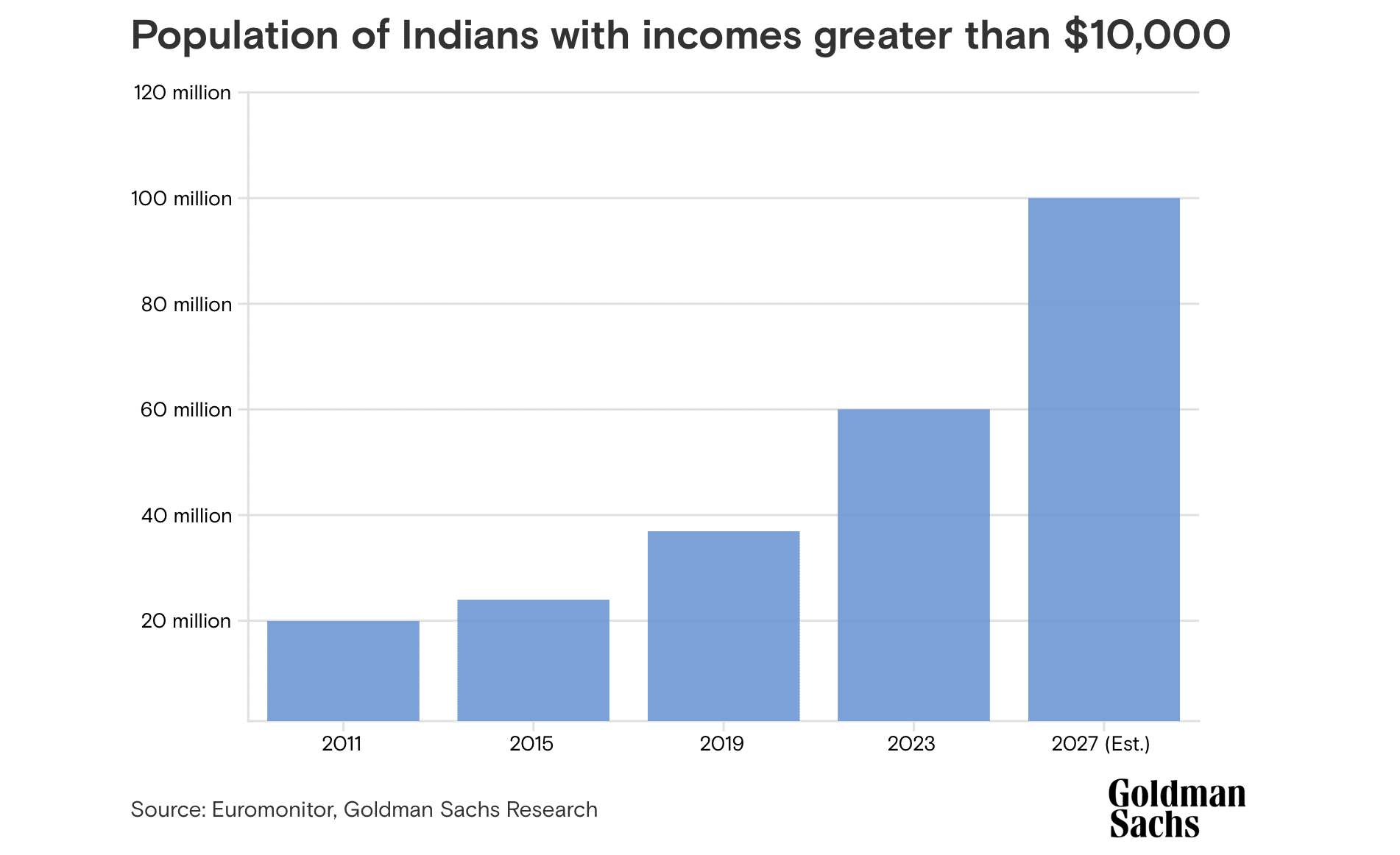

> Goldman Sachs stated in a report, “The Rise of Affluent India” in Feb. that the number of affluent consumers in India will grow from approximately 60 million in 2023 to 100 million by 2027.

> According to Knight Frank’s annual Wealth Report, the number of ultra-high-net-worth individuals (with a net worth of over $30 million) is projected to increase from 13,263 in 2023 to 19,908 by 2028.

> In 2023, luxury brands rented 600,000 square feet of space, up from 230,000 square feet the year before, marking the highest leasing in six years, per CBRE data.

Amid a rising demand for luxury goods in India has come a marked proliferation of counterfeits, which are plaguing luxury goods brands that have focused their energies on expansion in the country. “The problem is very serious. There are a lot of fakes [in India] of high-value, expensive goods,” a senior official from the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry’s Committee Against Smuggling and Counterfeiting Activities Destroying the Economy (“FICCI CASCADE”), told Al Jazeera recently.

The comment comes in conjunction with FICCI CASCADE’s release of a counterfeiting-focused report, which stated that the market for counterfeit (or otherwise infringing) apparel and textiles as of the end of 2023 is worth upwards of $4 billion, thereby, accounting for more than half of the total market.

The impact of this can be seen in the enduring rise of successful enforcement efforts by brands in India in recent years. Lacoste, for one, recently prevailed in a long-running lawsuit that it waged against “copycat” brand Crocodile International, with the Delhi High Court issuing an order this summer, in which it ordered the latter to permanently refrain from using marks that infringe Lacoste’s trademark rights.

Before that, Supreme landed a win in a trademark fight in India, with the Delhi High Court finding that its box logo amounts to a “well-known” trademark when used on “apparel and clothing.” And fast fashion giant similarly landed a win in a trademark infringement case around the same time.

Christian Louboutin has been waging a trademark-centric case before the High Court of Delhi as a result of the sale of shoes that infringe its well-known marks. And more recently, in a different segment of the market, Tesla sued an Indian battery maker this spring for alleged infringing its trademark by using the brand name “Tesla Power” to promote its products.

In light of the attractiveness of the Indian market and the increasing robustness of the market for counterfeits, cases will undoubtedly continue to be filed by global brands with increasing frequency. Stay tuned for more on this.