In 1917, a small Massachusetts-based footwear company called Converse Rubber Shoe Company introduced an athletic shoe. Unsurprisingly, given the company’s name, the sneaker that founder Marquis Mills Converse created – called the “Non-Skid” – consisted of a rubber sole, crafted from his proprietary “light gravity compound.” Thanks to the court-friendly nature of its signature shoe sole, as well as an early endorsement from professional basketball player Charles “Chuck” Taylor, Converse’s sneaker would become an in-demand offering among athletes, helping the company to amass more than 70 percent of the basketball shoe market by the 1960s.

At the outset, the “Non-Skid” sneakers were aimed at basketball players who wanted to “win,” according to a 1920 Converse advertisement, but the shoe – with its almost entirely unchanged vulcanized rubber sole, rubber toe cap, slim lace-up body, and signature All-Star patch – would ultimately attract a much larger pool of wearers. As the New York Times wrote almost 100 years after Converse first dreamt up its since re-branded Chuck Taylor All Star sneaker, “First came the athletes, then the greasers. Then came the nonconformists, the teenagers and finally the baby boomers.”

And do not forget the fashion pack. Brands, ranging from John Varvatos and Missoni to Comme des Garcons and Maison Martin Margiela, among many others, rushed to put their spin on Converse’s classic footwear offerings by way of large-scale collaborations.

Most famously, though, Elvis Priestley, James Dean, Kurt Cobain, Andy Warhol, and members of Led Zeppelin, The Beatles, The Sex Pistols, and The Ramones were just a few of the individuals who have been drawn to Converse’s simply-designed shoe style. In short: “The shoe manufacturer has sold its brand of cool and whiff of rebellion to generations of Americans” – and beyond, as the Times so aptly put it in 2014.

As of 2014, Converse had sold more than 1 billion pairs of its Chuck Taylors. The now-Boston-headquartered company – which had flirted with its demise just over 10 years earlier – was a long way from its 2001 Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. Thanks to a rescue – and extensive strategic revamp – courtesy of Nike, Converse went from bringing in just over $200 million in revenue in 2002 to generating nearly $2 billion in 2014, and the Chuck shoe style was responsible for the majority of those sales.

While Converse was busy growing at what has been characterized as a “breakneck pace” both on its home turf and internationally under Nike’s watch, it had reached its limit on one front. Tired of being the target of seemingly endless and truly uninterrupted copying, the brand made a bold move on an otherwise ordinary day in October 2014.

In a sweeping trademark crackdown, Converse name-checked 31 different brands and retailers, filing a whopping 22 different infringement lawsuits against the likes of Ralph Lauren, Tory Burch, H&M, Aldo, New Balance, Ed Hardy, FILA, and Wal-Mart, among others, for allegedly copying its then-106 year old staple Chuck Taylor shoe.

In each of those cases, all of which were filed in federal court in Brooklyn, New York, Converse alleged that the more than 2 dozen companies were “mass-producing, distributing or selling sneakers that knock off the look of [its] iconic Chuck Taylor.” They were running afoul of its trademark – or more specifically, trade dress – rights by replicating the various elements that make up the design of its Chuck Taylor sneakers, from the “distinctive” toe caps and toe bumpers to the striped midsoles.

On that very same day, October 14, 2014, Converse went a step further. In addition to suing those 31 companies in federal court, seeking injunctive relief and hefty monetary damages, it filed a separate complaint with the International Trade Commission (“ITC”). Converse wanted more than money from the defendants; it wanted to stop the allegedly infringing footwear from entering into the United States in the first place. Given its broad power to enjoin the importation of unlawful articles by way of general exclusion orders, the ITC could very well make that happen. But it wouldn’t be fast.

More than five years after Converse made headlines thanks to its barrage of legal actions, almost all of the 22 civil lawsuits have settled out of court, with many of the defendant brands and retailers presumably offering up a settlement sum and a vow not to make and/or market footwear that infringes Converse’s Chuck Taylors in order to make the cases go away. And while no more than three of those original 31 companies are still party to the ITC proceeding (due to settlements or defaults), one footwear-maker, in particular, has emerged as an aggressive opponent: Skechers.

In December 1992, L.A. Gear’s Robert Greenberg sold his 34 percent stake in the company he had founded just as its popularity was beginning to really wane, and started a new project. From his home in Manhattan Beach, the coastal town located about 25 miles from downtown Los Angeles, Greenberg – who, as Forbes puts it, “tried a lot of different ways to make money, including running a hair salon, starting a wig wholesaler, importing antique clocks, selling electronic tweezers, and operating a roller skate shop, before finding success in shoes” – founded Skechers, the affordable footwear company that would be his grand slam.

Generating some $4.64 billion in revenue per year as of 2018, the almost 30-year-old Skechers is the third largest player in the U.S. sneaker market, a title that has not come without it making enemies of at least some of its closest peers. Converse’s parent company Nike, for instance, has publicly decried in legal filings of its own that as driven by Greenberg, who simply “gives orders to knock-off competitors’ [successful] products,” Skechers has made it its mission to copy – or “Skecherize” – the best-selling creations of its rivals in its quest to gain market share in the more than $58 million global sneaker market.

On that list of “copycat” wares? A number of sneaker styles that bear a striking resemblance to the offerings of Converse, the very styles that landed it on the receiving end of one of Converse’s 22 trademark lawsuits and on the long list of companies it put forth to the ITC in mid-October 2014.

Tasked with conducting investigations on matters involving international trade, including ones that stem from claims of intellectual property infringement, in the fall of 2014, the ITC was presented with what would become one of the more closely watched trademark proceedings to date: the matter of “Certain Footwear Products,” i.e., Converse’s case.

Following a period of discovery and preliminary findings that centered on Converse’s rights in its signature Chuck Taylor All Star sneaker, the federal agency issued a highly-anticipated determination in June 2016 in which it invalidated one of Converse’s trade dress registrations, while issuing a sweeping exclusion order prohibiting the import of any shoes that infringe other marks of the footwear company.

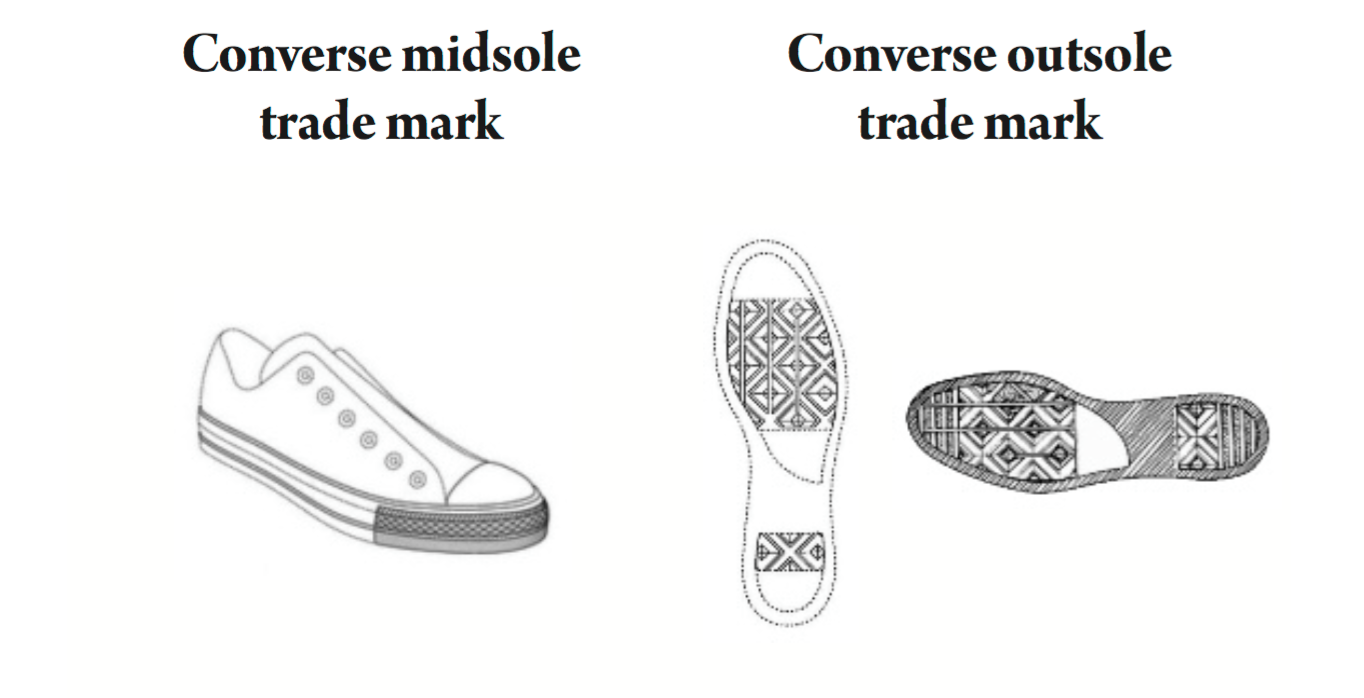

In a blow to Converse’s case, the ITC took issue with one of the registrations upon which the company was so heavily relying – the broad “midsole” mark that covers the Chuck Taylor All Star’s “two stripes on the midsole of the shoe, the design of the toe cap, the design of the multi-layered toe bumper featuring diamonds and line patterns, and the relative position of these elements to each other.”

According to the ITC, Converse’s “midsole” registration was not infringed – by Skechers or the other alleged copycats – but not because of a lack of similarity between the brands’ shoes. No, the ITC failed to find infringement because the registration that Converse referenced did not yet exist when Skechers and co. first began selling the allegedly infringing footwear. While Converse had been using the midsole trade dress since 1932, it did not receive a federal registration for it until 2013.

In addition to pointing to a U.S. registration for the “midsole” trade dress, Converse also cited common law rights for the “midsole” as a result of its use of the mark in commerce. After all, trademark and trade dress rights are gained in the U.S. by actual using that mark and not by applying for and receiving a registration from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Yet, the ITC similarly pushback against Converse’s claim of rights, stating that the company also lacks common law rights because the “midsole” design is devoid of the secondary meaning (i.e., evidence that consumers link that specific design to a single source) that is a pre-requisite for the protection of a product design, such as that of a shoe.

As a result of the ITC’s findings, Skechers was off the hook for at least some of the infringement liability it was facing, namely for its Twinkle Toes and BOBS Utopia shoe styles.

That was not the whole of the ITC’s decision, though. In a favorable development for Converse, the ITC found that two of its other trade dress registrations– those extending to the design of the soles of its Chuck Taylor sneakers, namely the elements that make up the shoe’s the diamond-patterned outsole – are valid and enforceable, and that Skechers’ shoes were infringing. As such, the ITC issued an exclusion order blocking any non-Converse shoes with infringing soles – including but not limited to Skechers footwear – from entering into and being sold in the U.S.

With a partial victory in hand, Skechers boasted about what it characterized as a “major win” in a widely circulated press release, just as it has made a habit of doing in each round, and just as in rounds before (and to come), no small number of media outlets bought into Skechers’ very specific narrative, and declared it the victorious party.

But its victory would be short-lived. Converse – unsatisfied with the ITC’s findings in connection with its “midsole” mark – filed an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and in October 2018, a 3-judge panel held that the ITC had “applied the wrong standard in aspects of both its [trade dress] invalidity and infringement determinations.” As such, the court remanded the case back to the ITC for proceedings focused on whether secondary meaning existed in the Converse sneakers as of the date of Skechers and co.’s first infringement and whether the allegedly infringing sneakers are substantially similar to Converse’s trade dress.

Back before the ITC in October, the Chief Administrative Law Judge Charles Bullock issued his Initial Determination on Remand. He held – in short – that while Skechers’ Twinkle Toes, Bob’s Utopia and the Hydee Hytop shoes do not infringe Converse’s trade dress rights, the brand’s Daddy’$ Money shoes do infringe Converse’s “midsole” mark, as the inclusion of Skechers’ branding on the since-discontinued Daddy’$ Money shoes is “not enough to overcome the substantial similarity” and likelihood that consumers will be confused about the source of the shoes.

Nonetheless, Judge Bullock ultimately let Skechers off the hook for the allegedly infringing footwear (and thus, liability under the U.S. Tariff Act’s prohibition on unfair trade or unfair competition in importation), since it had previously been determined that Converse’s “midsole” mark (either its common law rights or its trade dress registration) was not valid or enforceable.

Still not a closed-case, on October 22, Converse, Skechers, and the other active respondents each filed a petition for review of Judge Bullock’s decision. The ITC, itself, has since extended the date for determining whether to grant a review of the decision to January 24, 2020, and has also extended the target date for completion of the investigation to March 24, 2020.

According to language in the Form 10-Q that it filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission last month, Skechers says that “it is too early to predict the outcome of [the ITC proceeding and the still-pending civil suit] or whether an adverse result in either or both of them would have a material adverse impact on our operations or financial position,” but notes that it believes it has “meritorious defenses and intends to defend these legal matters vigorously.”

As for Converse, its parent company Nike noted in the unrelated patent infringement lawsuit that it filed against Skechers in late October that the the two parties have a history.

“This is not the first time Skechers has infringed [Nike’s] intellectual property rights,” the sportswear giant asserted in its suit this fall, and in fact, Nike declared, “This is the fourth lawsuit in a series of lawsuits that Nike, and its subsidiary Converse Inc., have filed against Skechers asserting a range of intellectual property rights,” including the still-ongoing proceedings that Nike-owned Converse initiated before the ITC, the lawsuit that Nike filed over Skechers’ copycat knitted sneakers, and the design patent infringement case that Nike filed against Skechers in September.

In other words, the ongoing Converse v. Skechers cases are just one part of one of the fiercest legal rivalries in the notoriously litigious footwear space, and also part of Converse’s quest to claim what it views as design elements that are rightfully its own.