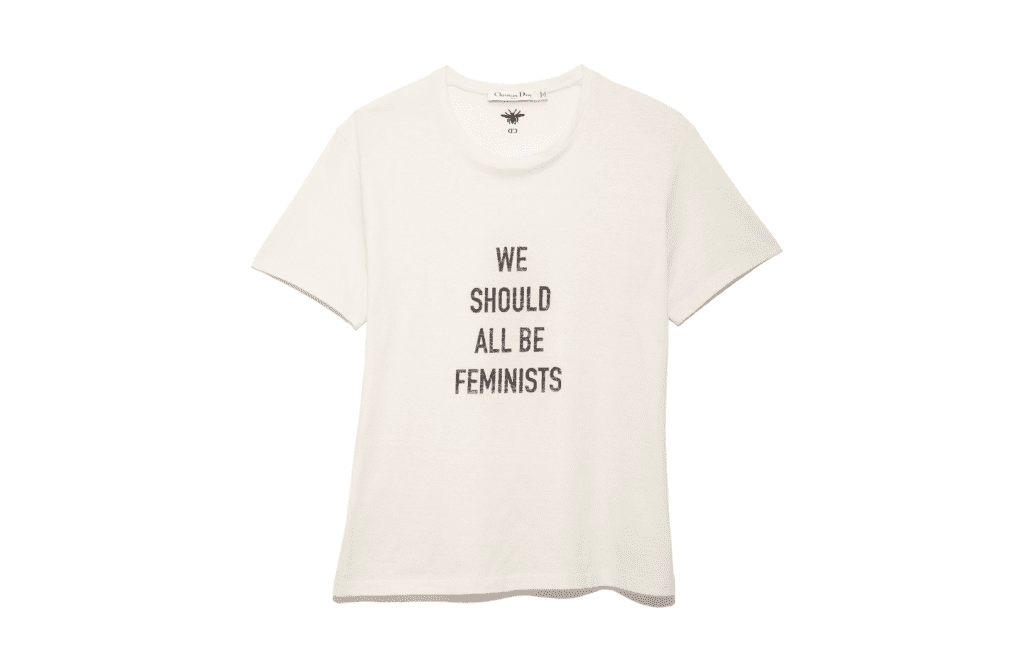

Evening bags that read “Pussy Power” hit the runway during one of the first big-name womenswear shows of the Fall/Winter 2018 season last year. “New York fashion shows to highlight #MeToo movement,” read a headline from Reuters. Right around the same time, Rebecca Minkoff released, in lieu of a fashion show, a collection of feminist-focused garments; the release was rather timed perfectly with the 2018 Women’s March. And not to be forgotten: the various feminist-inspired statement tees that Dior has been trotting down the runway in recent seasons. The brand’s $800 “We Should All Be Feminists” t-shirt immediately comes to mind. While these might be noteworthy efforts in raising awareness about gender equality, they are not enough.

If the fashion industry is truly serious about change (and not merely relying on women’s rights and gender equality/empowerment as the latest hot-selling trend, as many appear to be doing), there are two things it could do: 1. Pay women that are doing the same jobs as men with the same level of experience as those men equally. 2. Ensure that all employment contracts are devoid of mandatory arbitration clauses for sexual harassment and discrimination claims.

Tangible action on these two prongs, which would occur on paper and for the most part, behind-the-scenes, is not nearly as flashy or Instagrammable (and thus, marketable and monetizable) as, say, a “Girl Power” t-shirt or a #MeToo-themed runway show. However, taking steps to ensure that women are not discriminated against in terms of pay and/or promotions (as Nike, Italian design house Etro, and i-D, Vice, and Garage magazine publisher Vice, for instance, have allegedly done for quite some time according to currently pending lawsuits), and to safeguard their right to have access to the legal system every year so harassment and discrimination claims may be adjudicated, are much more meaningful endeavors than over-priced designer wares.

Putting aside (just for now) the rampant gender-based inequality in pay and promotional standards, and the striking lack of equality at the helm of major houses, in the C-suite, and on executive and advisory boards that is prevalent in fashion, consider an immensely important but rarely discussed issue that should be at the center of fashion’s efforts to address the role of women in the industry: how most companies handle women’ claims of sexual harassment and discrimination.

As we noted last month, a significant reason why sexual harassment continues to permeate workplaces, including fashion ones, stems from how these claims of wrongdoing are handled procedurally. No small number of companies require individuals, as a condition of their employment, to sign contracts that contain a mandatory arbitration clause, such a provision stipulates that the employee will be required to resolve a dispute with his/her employer, including charges of sexual harassment, through arbitration and thus, not before a court of law.

As a practice, arbitration differs, in part, from formal litigation in that its proceedings are private (meaning that third parties cannot attend arbitral conferences and hearings), and in some cases, are completely confidential, thereby obscuring information about the proceedings from the public. More often than not, the participants in an in-house arbitration are forced to sign confidentiality agreements as a prerequisite to the settlement of the claims.

Additional considerations abound, including the fact that such out-of-court proceedings are overseen by arbitrators – or individuals that are not trained as judges – and as legal and employment experts have argued, there is a limited amount of objectivity in arbitration, at least in part because the process of choosing an arbitrator is not inherently unbiased. Since private arbitrators are usually selected and compensated by the parties to resolve a dispute (i.e., the employer), they stand to “generate inherent conflicts of interest, including the [arbitrator’s] pursuit of repeat business from high-volume customers.”

In short: “Payments to free market referees raise particular concerns insofar as referees may be influenced to decide cases in favor of the party more likely to bring cases to them in the future,” which would be the employer, as set forth by the court in Benjamin, Weill & Mazer v. Kors. (Note: The American Arbitration Association said it allows those initiating an arbitration action to reject arbitrators on the ground of potential bias).

In case that is not enough, many employment contracts include class action waivers. This are contract provisions that: 1) require employees to agree to refrain from filing class action lawsuits; 2) require them to, instead, handle legal matters by way of arbitration; and 3) require employees to handle such matter via arbitration on an individual basis, i.e., not with other employees.

Companies that have class action waiver provisions in their employment contracts have argued that there are benefits to requiring employees to bring claims individually: “Claims are better settled on a case-by-case basis, thereby, resulting in quicker and more efficient decisions,” as noted by NPR.

The flipside, which has been argued by no small number of workers’ rights advocates, is that by requiring employees to make their cases in individual arbitrations, “the process often isolates workers from each other, when they most need the resources and information-sharing so crucial to establishing patterns of misconduct.”

Companies’ large-scale reliance on quiet arbitrations, including the usage of class action waivers (the legality of the latter is being decided by the Supreme Court as we speak), has enabled sexual harassment to become institutionalized in corporate culture, according to lawmakers and researchers, alike.

As for exactly how common arbitration clauses and class action waivers are in fashion, that is difficult to pin-point. However, it is absolutely worth noting that no shortage of industry cases – ranging from those filed several years ago against Nasty Gal for gender and pregnancy discrimination and Forever 21 for transgender discrimination to American Apparel and its founder Dov Charney for sexual harassment, just to name a few – have been dealt with by way of mandatory arbitration.

These cases are likely representative of a much larger number pool of cases and a truly expansive number of fashion brands, publications, and other industry companies, such as PR firms and model management companies, that make use of such provisions.

So, if fashion industry participants really want to affect change (and I mean actual change), it will take more than a t-shirt, and will require, among other things, removal of arbitration clauses and class action waivers from employment contracts. Now. And while we are at it, instead of selling products declaring the need for gender equality, let’s pay women at the same rate as men for the same work.

*This article was initially published on February 9, 2018.