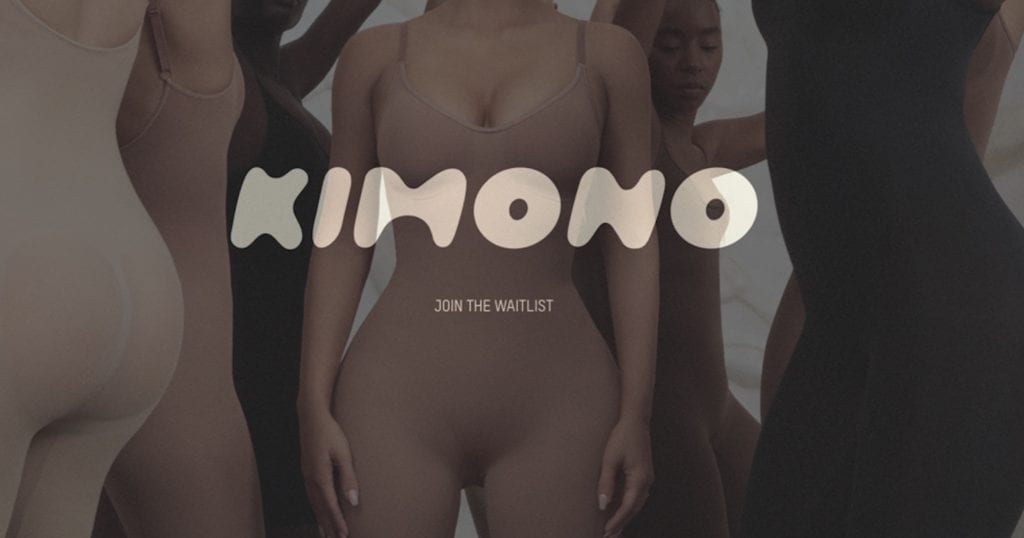

From the Supreme Court case centering on the name of celebrated streetwear brand fuct to Kim Kardashian’s big reveal of her controversially-named Kimono shapewear collection, trademark law has been in fashion/pop culture news with marked frequency this week – and with it, some notable misconceptions about what trademark protection actually entails.

One of three main types of intellectual property in the U.S., along with copyrights and patents, trademark law provides protection for any word, name, symbol, device, or any combination thereof, used to identify and distinguish the goods/services of one company from those of another. For example, the Gucci name signifies a single source of products – the Gucci brand – to consumers, just as the appearance of a swoosh on the side of a pair of shoes alerts consumers that the footwear is a product of Nike. The instantaneous leap that is made in the minds of consumers between a name or logo to the corresponding brand is the very epitome of source designation, and thus, a clear demonstration of the purpose – and power – of trademarks rights.

In the U.S., these rights are established by use, meaning that a trademark registration is not required in order for rights to exist. However, assuming you were to file a trademark application and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) issues a trademark registration for your brand’s name, what do you get? For one thing, you get the “exclusive right to use the mark nationwide in connection with the goods/services listed in the registration,” per the USPTO. More than that, you get the right to file trademark infringement lawsuits in federal court should another party use your mark on “competing or related goods and services” in a way that is likely to lead to consumer confusion.

Maybe even more telling, though, is what you do not get when a trademark registration is issued. One thing you definitely do not get is a sweeping, no-holds-barred monopoly on the word (or logo) at issue. That is because a trademark registration only entails nationwide rights for use of a mark – and for the enforcement of that mark – in connection with the goods/services that you actually make/sell, and ones that could be deemed related.

What else do you not get? You do not get the right to prevent others from using your trademark in a non-source identifying capacity. In other words, you can only prevent others from using your trademark if they are actually using it as a trademark. This is best explained by way of an example. On Wednesday, one fashion site stated in its coverage of the widespread cultural appropriation claims being lodged against Kim Kardashian over the name of her Kimono shapewear collection, “Some [media] outlets have reported that West has trademarked the word, meaning Japanese companies importing the garment to the USA would have to do so using a different name for the style.” That is not true.

In fact, as of May 28, the USPTO pushed back on at least one of the applications, noting that it “includes wording that is indefinite, overly broad, and/or includes goods or services in multiple classes.” Moreover, the USPTO stated in connection with the “Kimono Solutionwear” and “Kimono World” marks that Kardashian “must disclaim the word ‘KIMONO’” because it is an “unregistrable term [that], at best, is merely descriptive of a function of applicant’s goods/services.”

With the foregoing trademark tenets in mind, we know that Kardashian’s rights in the “Kimono” trademark are limited: they are limited to the types of goods and services for which she is actually using the trademark (and potentially, “related goods”).

If we consider the most recent trademark application for registration filed by Kardashian’s counsel in June for “the word ‘KIMONO’ in a stylized font” for use on everything from bags and wallets to shapewear and you guessed it … robes and “kimonos,” her rights will be limited in more ways that one. For one thing, trademark law does not provide protection for generic marks, (i.e., the name of the good or product offered), which means that Kardashian will not enjoy protection for the word “Kimono” for use on kimonos and probably not robes for that matter, either. Beyond that, because her rights in the stylized “Kimono” mark extend to both the word “Kimono,” as well as the specific font, Kardashian’s ability to claim trademark infringement is narrower than if the “Kimono” registration did not make use of a particular font.

Still yet, her enforcement abilities are exclusively limited – across the board – to instances in which the unauthorized uses of the “Kimono” name are done in a way that indicates the source of the allegedly infringing products. Chances are, this will be a rarity, in large part because kimono is a term that identifies a type of garment, and most uses of it are doing just that – identifying or describing a certain garment, not purporting to pin-point the source of that garment. With that in mind, Gucci and the “Silk Kimono Jacket” it is currently selling would not fun afoul of Kardashian’s rights because such use is descriptive of the product. The same goes for Haider Ackermann’s “Men’s Brown Kimono Shirt,” Fleur du Mal’s “Haori Kimono,” Johanna Ortiz’s “New Sunrise velvet kimono,” and Etro’s “floral print kimono” – all of which are currently on the market.

In short: regardless of Kardashian’s trademark rights (assuming she has some), brands can still call a kimono a kimono without infringing those rights/suggesting that their robe-like garments are in any way connected with Kardashian and/or her brand, i.e., they can continue to use the word in a descriptive, non-trademark capacity. Kardashian’s team understands this. In a statement on Thursday provided to the New York Times, Kardashian said, “Filing a trademark is a source identifier that will allow me to use the word for my shapewear and intimates line but does not preclude or restrict anyone, in this instance, from making kimonos or using the word kimono in reference to the traditional garment.”

As for the sweeping cultural insensitivity issues that at play here in connection with the American mega-star’s co-opting of the Kimono name for a collection of undergarments with no apparent ties to Japanese culture at all, the Los Angeles Times’ Tracy Brown put it like this: “Kardashian West’s appropriation of the word ‘kimono’ for a line of products that have nothing to do with kimonos is problematic because it completely removes the word from any cultural or historical contexts,” including the “the complicated American history around people of Japanese descent and Japanese culture.”

Kardashian’s branding decision, Brown states, “ignores and erases both Japanese tradition and very specific Japanese American experiences” – such as the the widespread internment and “encouraged ‘Americanization’” of some 120,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them U.S. citizens, during World War II” – in order to “create a brand around a word that is already loaded with meaning. Meanwhile, Kardashian told the Times that she is not going “to design or release any garments that would in any way resemble or dishonor the traditional [kimono] garment,” and is not changing the name. Instead, she stated, “My solutionwear brand is built with inclusivity and diversity at its core and I’m incredibly proud of what’s to come.”

UPDATED (June 29, 2019): The Mayor of Kyoto addressed a letter to Kardashian, requesting that she withdraw her trademark applications for “Kimono” and rename her brand.

UPDATED (July 1, 2019): Kardashian confirmed in an Instagram post that she will change the name, although the various trademark applications for “Kimono” that were filed with the USPTO have not yet been withdrawn.

UPDATED (August 26, 2019): Kardashian has confirmed by way of an Instagram post that the name for the collection will be SKIMS.