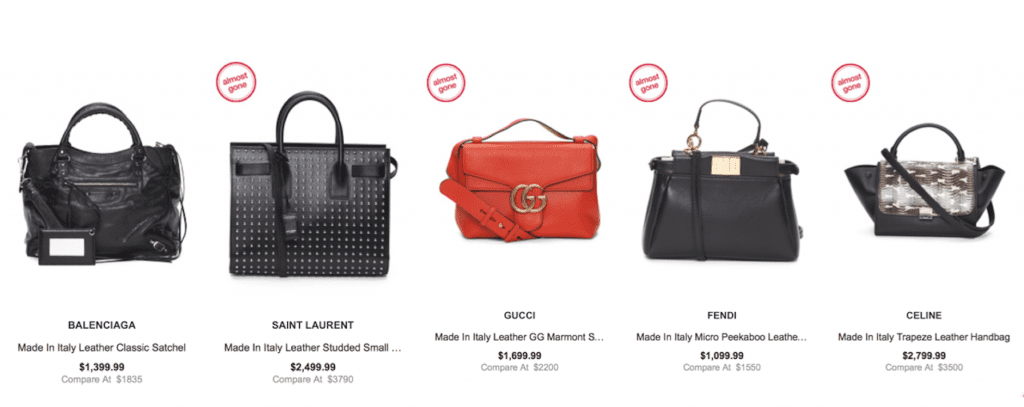

T.J. Maxx, Marshalls, and a number of other similarly situated retailers boast websites and/or brick-mortar-stores that stock designer bags and garments for less, and make a killing as a result. T.J. Maxx, for instance, is currently stocking an array of in-season Gucci, Fendi, Yves Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga bags for several hundred dollars less than other retailers. In terms of garments, they stock the likes of Givenchy, Missoni, Céline, Pucci, Dior, and Dries Van Noten – just to name a few.

But are these authentic products, and if they are … how is this distribution model legal?

TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE?

According to most accounts, the bags – and garments – that retailers like T.J. Maxx and Marshalls sell are generally accepted to be authentic goods. The general lack of lawsuits initiated by brands in connection with the sale of counterfeit goods by these retailers also serves as a striking inference in terms of authenticity of the products.

As for the pricing of such goods (85 percent of which is the same as the seasonal merchandise in mainstream department stores, according to TJX), Seeking Alpha’s Matthew Worley noted that discounts are not a mere “10 percent off other department stores’ prices, but closer to 50 percent and more,” and the low prices center largely on how they negotiate with designers, and how they advertise.

Worley states, “T.J. Maxx doesn’t include a buy-back clause with their designers – which ups the price from the designers – as big department stores do.” Buyers at T.J. Maxx and Marshalls have forsaken this privilege of return in order to cut better deals with designers, and as a result, they do not pass such added costs on to the consumer. Moreover, T.J. Maxx and Marshalls bypass quite a bit of the 300 to 400 percent mark-ups that many retailers tack on to the cost of a good.

UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION

The legality of this off-price retailer distribution model is complicated. A surprising number of brands – even at the upper end of the luxury spectrum – offload unsold merchandise to discount chains at the end of each season, directly or by turning a blind eye to authorized retailers that act out.

In terms of dealing with unsold products, luxury brands have traditionally taken a different approach. Louis Vuitton, for instance, goes to great lengths to avoid selling off old garments and accessories at discounted prices; the Paris-based luxury brand is said to destroy all of its unsold merchandise at the end of each year. Chanel, on the other hand, puts some goods – garments only – on sale in its boutiques bi-annually. And Hermès holds sample sales, devoid of Birkin and Kelly bags, of course.

Yet, many of those brands’ wares end up on discount racks. According to a statement from T.J. Maxx, “We buy from all kinds of vendors, and we take advantage of a wide variety of opportunities, which can include department store cancellations, a manufacturer making too much product, or a closeout deal when a vendor wants to clear merchandise at the end of a season, as well as lots of other ways.”

This broad language tells us very little in actuality, but what we do know is that stores ranging from Macy’s and Nordstrom to Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman employ buyback clauses in their contracts with brands, in which the brands are required to buy back merchandise that does not sell on their own dime. With that in mind, buying back these products and then off-loading them to off-price retailers (which then drastically reduce prices, and offer the goods for sale in their stores) is in the best interest of brands’ immediate bottom lines.

However, this model – and the fashion media in general – does little to explain how the wares of traditionally off-price retailer averse brands, such as Yves Saint Laurent or Céline, end up in T.J. Maxx. And rather unsurprisingly, the brands have been less than forthcoming in terms of shedding light on how such distribution comes to light.

Our research indicates that one way for in-season Gucci bags, for instance, to land in T.J. Maxx stores is if T.J. Maxx buyers source them from the brand’s authorized stockists. Such purchases may come from Nordstrom, which stocks YSL, Fendi, Givenchy, and Dolce & Gabbana bags, among others from similarly situated brands.

According to sources, T.J. Maxx and Marshall’s buyers are prone to acquiring just about everything that can be found in mainstream department stores, such as Macy’s and Nordstrom. While this would be a legitimate transaction for T.J. Maxx, it would likely be a breach of contract on the part of Nordstrom, as Nordstrom almost certainly agreed in the terms of its distribution agreement with YSL to refrain from selling to unauthorized retailers and/or selling in bulk to any entity.

As Eric Wilson noted in an article for the New York Times several years ago, “Readers of the fine print on the sites of luxury retailers like Saks Fifth Avenue, Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman may be surprised to discover that a policy [that limits the number of units of a particular style that a customer may buy] now applies to designer handbags.” Wilson noted that such policies cite “popular demand,” as the reason as to why “customers may order no more than three units of these items every 30 days.”

This is not the whole story, though. Such clauses are likely in place to keep consumers – and retailers – from engaging on price arbitrage and fueling the gray market. As Wilson notes, “On its face, the policy sounds odd; that is because it really doesn’t have anything to do with popular demand. Rather, it is the fear that foreign buyers, taking advantage of the severely weakened United States dollar, will hoard the bags, then resell them in Europe or Asia, where the same items in Prada and Gucci stores typically cost 20 to 40 percent more.”

In reality, such terms – which mirror Louis Vuitton’s terms that no consumer may purchase more than three bags at any given time, no more than two of any style per year, and on its website, consumers may only purchase between one and two of any given style – aim to thwart gray market sales.

GRAY MARKET GOODS

What about luxury branded products, like Céline and Christian Dior, which have not traditionally sold garments or bags through third party retailers (only by way of brand-owned and operated stores)? The gray market is one of the most likely explanations for how Céline bags are available for sale – albeit in extremely limited quantities – in T.J. Maxx and Marshalls stores.

(Note: Quite often these pricey bags serve as a bait-and-switch type advertising tactic to simply get consumers into their stores. Because these consumers will likely purchase other, more affordable goods – and not the $1,000+ bags – a small quantity of these bags will do the trick, so to speak).

Gray market goods, also known as parallel imports, are genuine products protected by copyright, trade mark or patent rights that are imported into a country without the authority of the intellectual property rights owner in that country. This is how Costco was able to get its hands on and sell an array of Omega-branded watches – even though Omega maintains a rather strict network of distributors, which much be authorized by the watchmaker. It may also be how unauthorized retailers are able to boast stock that includes luxury handbags.

As we learned from the Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. case, which the Supreme Court decided in March 2013, a copyright holder cannot rely on the U.S. Copyright Act to prevent the unauthorized importation and resale of copyright-protected works, even if they have been manufactured abroad.

In terms of trademark-protected goods – such as logo-bearing bags – the general rule is similar. It holds that “a trademark owner’s authorized initial sale of its product exhausts [his] right to maintain control” of that product. The exception: Gray market imports can be unlawful when “material differences” – ones that would cause consumer confusion, dissatisfaction, and irreparable harm to the trademark holder – exist between such imports and the authorized goods. Not surprisingly, there is not a bright line rule as to what “material differences” actually means.

However, the Fifth Circuit court in Martin’s Herend Imports v. Diamond & Gem Trading USA stated of imported figures: “Some of the pieces were completely different pieces from those sold by Martin’s. Others had painted patterns and colors different from those offered by Martin’s. As a matter of law, such differences are material [and the importation of the goods thus infringing].”

With these legal doctrines in mind – and assuming that any bags or garments offered by these retailers are authentic and not “materially different” from the brand’s authorized goods – discount retailers’ acquisition of goods by way of the gray market will likely be deemed perfectly legal. This does not bode well for notoriously protective luxury brands that tend to detest the sale of the goods outside of authorized distribution chains. It is great news, however, for consumers looking to stores like T.J. Maxx and Marshalls for deals on Fendi bags.

But then again, one could argue that brands very well may be turning a bit of a blind eye and keeping their mouths shut to such practices in order to maintain their premium positioning while reaping a benefit for their own bottom lines.

* This article was initially published in December 2016.