“A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes],” Mike Jeffries told Salon in 2006 explaining the culture of the brand he was tasked with overseeing at the time. “That’s why we hire good-looking people in our stores. Good-looking people attract other good-looking people, and we want to market to cool, good-looking people. We don’t market to anyone other than that.” That brand was Abercrombie & Fitch, of course, the traditional mall retailer known for its “clean and classic” apparel, its ad campaigns, complete with semi-nude models, and its explicitly exclusionary attitude.

This is something Jeffries, who had been hired in 1992 to revamp the brand (following its bankruptcy and subsequent acquisition by Limited Brands in 1988), would freely admit. “Are we exclusionary?,” he asks himself aloud. “Absolutely.” The rationale behind Jeffries’ flippancy: “I don’t want our core customers to see people who aren’t as hot as them wearing our clothing.”

Jeffries, himself, came of age in Los Angeles (hence, his bleach blonde hair and penchant for the word “dude”) before studying at the London School of Economics and Columbia Business School, where he would earn his MBA. He joined Abercrombie from Paul Harris, a Midwestern women’s chain, at age 48, and despite his wildly controversial public dialogue about Abercrombie’s revamp, within just a few years as CEO, he had succeeded in crafting the retailer into one of the hottest brands of the 1990’s.

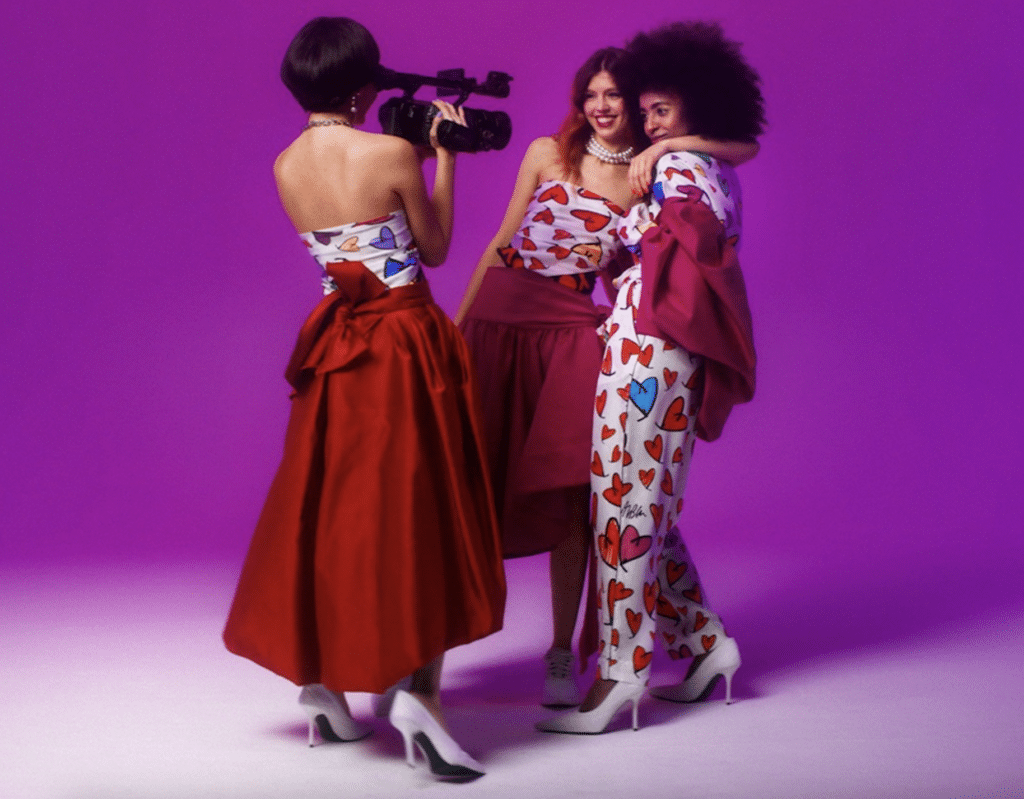

In its heyday, Abercrombie boasted a network of 700 dimly-lit and thoroughly-fragranced stores, boasting 22,000 strikingly attractive employees and nearly $2 billion in annual sales. The entrance ways of the individual stores, almost always located inside a mall, were flanked with shirtless teenage boys, the walls covered with Bruce Weber-lensed ad campaign imagery of more toned and tanned teens. The music was loud and the offerings – A&F logo-ed tees, $90 distressed jeans, and ripped denim skirts, which went up to size Large (no XL for girls and certainly no XXL) – were irresistible to teens that wanted to embody the lifestyle that the brand was selling and that could afford to do so.

The Look Policy

By the early-to-mid-2000’s, Jeffries had, irrefutably, taken the dusty 100+ year old casualwear brand and turned it into one of the most relevant destinations for all-American collegiate types. In large part, Jeffries – who was bringing in $71.8 million in compensation as of 2007 – succeeded thanks to the wildly specific branding he put in place.

Abercrombie was an apparel business, with its relatively pricey mini-skirts and house-branded polos, but beyond that and under the direction of Jeffries, the retailer was most certainly selling sex. And it was only selling it to “good-looking, cool kids,” according to the former CEO. This is where the retailer’s now-notorious “Look Policy” came into play. Specific guidelines on everything from the color and length of employees’ hair to the specifics of girls’ makeup (“must be worn to enhance natural features and create a fresh, natural appearance,” per Abercrombie rules) to the length of fingernails helped to ensure that, as Forbes put it, “the sales clerks all looked like your biggest high school crushes.”

Treating hiring like model castings also worked to further this narrative: “Store managers would often approach attractive white customers who had the ‘look’ and urge them to apply for sales jobs,” according to Think Progress. It was imperative for Jeffries – who reportedly made “every decision, from the hiring of the models to the placement of every item of clothing in every store” – that everyone from the greeters in the stores’ entryways to the individuals behind the cash registers looked the part. That “looking the part” requirement was observed so strictly that according to a discrimination lawsuit filed in June 2003, any Asian-American, African-American, and Latino individuals who were hired by Abercrombie were relegated to stockrooms where those staffers could not be seen by customers. The retailer settled the class action suit a year later, agreeing to pay $40 million to put an end to the litigation in November 2004.

The retailer also revealed that it as part of the lawsuit settlement would appoint a Vice President for Diversity, who would report directly to Jefferies, in order to provide diversity training for all employees with hiring authority. Still yet, Abercrombie was also required to hire 25 recruiters to seek out minority employees, and prohibited from relying on previous recruitment strategies, including “targeting particular predominately white fraternities or sororities.”

That lawsuit was followed up by another headline-making case just over five years later, this time initiated by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed suit against Abercrombie after the retailer refused to hire Samantha Elauf, a young Muslim woman, arguing that because she wore a hijab (in accordance with her religious views), she did not comply with the company’s strict dress code. Despite a ruling from the Supreme Court that Abercrombie’s “Look Policy” ran afoul of federal law, the company was undeterred. (In its June 1, 2015 decision, the Supreme Court held that an employer may not refuse to hire an applicant if the employer was motivated by avoiding the need to accommodate a religious practice. Such behavior violates the prohibition on religious discrimination contained in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.)

Any doubts as to whether Abercrombie’s “Look Policy” – which was made clear via internal company documents and posters, such as its “Hairstyle Sketchbook” – was still being enforced to any meaningful extent after America’s highest court called foul were clarified when yet another lawsuit was filed against the retailer.

62,000 Employees

It was 2015 – one year after Jeffries retired from his CEO position in light of eleven straight quarters of same-store sales declines and after he was ousted as chairman of Abercrombie’s board of directors due to investor pressure – when Abercrombie was hit with another damning lawsuit. Former employees Alexander Brown and Arik Silva filed suit against the retailer in federal court in California, alleging that Abercrombie management required that its hourly workers purchase the brand’s clothing to wear on the job. In doing so, Abercrombie was, according to the lawsuit, running afoul of various state labor codes, including those in California, Florida, New York, and Massachusetts.

As Brown and Silva set forth in their complaint, Abercrombie policy “forced” employees to buy new Abercrombie clothes “each time a new sales guide came out.” In the suit, the plaintiffs further alleged that the retailer failed to reimburse them and other employees for such purchases despite obligating them to wear a specific “uniform.” In accordance with California, Florida, New York, and Massachusetts labor law, employers are required to reimburse any employee that is required to purchase a work uniform as a condition of employment or business-related expenses. Abercrombie did no such thing, per Brown and Silva.

What started as a seemingly small-scale lawsuit filed by two individuals turned into a legal bombshell when a California federal judge held that the case could be extended to a much larger pool of former and then-current Abercrombie employees. Overnight, the lawsuit went from having two plaintiffs to potentially allowing some 250,000 different individuals to join the fight. The case (which was removed from Alameda County Superior Court to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio in December 2017) was followed closely by another Fair Labor Standards Act suit, which was filed in federal court in California (and subsequently transferred to Ohio) by former Abercrombie employee, Alma Bojorquez, in June 2016.

In order to avoid trial and further litigation costs, Abercrombie agreed to settle the cases in January 2018 with a payment of $25 million, which it would put into a class settlement fund, a portion of which would be distributed to the plaintiff employees that were not reimbursed for Abercrombie apparel they purchased specifically to wear on the job. ($7.5 million would be used to pay the plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees and an additional $1 million would be used to cover administrative costs and other legal costs).

According to a statement from an Abercrombie spokeswoman: “Abercrombie & Fitch Co. and Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc. have agreed to settle two putative class action lawsuits and a national collective action case, originally filed in 2013, alleging that the company required its employees to purchase its clothing dating back to 2009. At that time Abercrombie had, and continues to have, clear written policies and associate handbooks in place that stated its employees were not required to purchase or to wear company merchandise, nor were they obligated to make use of their employee discounts.”

The spokesman further told TFL, “Abercrombie strongly contests the lawsuit allegations. However, it believes it is in the best interest of the company and all its stakeholders, including its employees, to settle this matter.”

As for Jeffries, he may have left Abercrombie in 2014, but his penchant for strict – and in some cases, downright illegal – branding techniques lives on. And as he put it during his tenure as CEO, “Do we go too far sometimes? Absolutely.”

The cases are Alma Bojorquez et al. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Co. et al., 2:16-cv-00551 (S.D. Ohio), and Alexander Brown et al. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Co. et al., 2:17-cv-01093 (S.D. Ohio).

* This article was originally published in January 2018.