image: atlasobscura

image: atlasobscura

The protectability of colors has been a recurring topic of interest in fashion for years, but particularly in the wake of the 2013 decision from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which held that Christian Louboutin does, in fact, have a valid trademark in “Chinese red” for use on the soles of shoes (as long as those shoes are not monochrome red). More recently, the European Union’s highest court sided with Louboutin in its latest battle over the red sole, holding that the red shoe sole is not incapable of enjoying trademark protection, as it does not fall within the absolute grounds for refusal.

It has not been all wins for Louboutin, though. The brand’s global trademark onslaught has experienced its share of ups-and-down. Just last spring, for instance, the brand suffered a loss in Switzerland, when the Federal Supreme Court in Lausanne affirmed a lower court’s 2016 decision, which classified the brand’s famed red sole as a “decorative element,” as opposed to an identifier of source. It is imperative that the color be used to identify a specific brand – and not merely be used in a decorative function – in order to classify as a trademark.

In its March 2017 decision, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court held that while Louboutin does maintain trademark protections in other countries, including the United States, China, Russia and Australia, that does not mean it is entitled to the same level of protection in Switzerland.

Back on U.S. soil, various consumer goods companies, although non-fashion ones, have been sparring over color. Last summer, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) held that General Mills’ 77-year old Cheerios brand could not claim exclusive rights over the yellow hue that adorns its cereal boxes. Why? Well, according to the TTAB, because too many other breakfast cereals also sell their products in yellow boxes.

Still yet, the TTAB held that due to the lack of uniformity with which Cheerios uses color generally – its varying types of Cheerios, for instance, which range from Chocolate and Frosted Cheerios to Honey Nut and Multi-Grain Cheerios, come in boxes of varying colors (some brown, others blue, still others are orange, etc.) – it is not convinced that “customers perceive … the color yellow alone, as indicating the source of [Cheerios’] goods.”

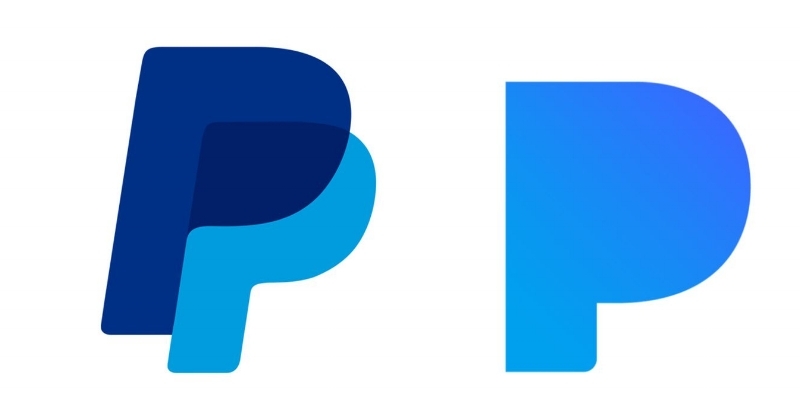

Right around the same time, PayPal and Pandora clashed over color, as well – the color blue, to be exact – which plays a prominent role in their respective logos. PayPal was prompted to file suit against Pandora after the music streaming service debuted a new logo last year – consisting merely of a blue-hued “P.”

PayPal’s logo (left) and Pandora’s logo (right)

PayPal’s logo (left) and Pandora’s logo (right)

According to the suit, which was filed in May 2017 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, in addition to adopting the simplified “P,” Pandora’s updated logo is problematic – and allegedly infringing – due to its use of “the same deep-blue color range” as PayPal.

The money-transfer company, which was founded in 1999 but Elon Musk and others, went on to mention Pandora’s use of color 11 different times in its complaint, pointing to “Pandora’s familiar deep-blue color range,” which is likely to confuse consumers as iPhone apps’ logos – and their color schemes – “play the critical role of serving as an identifier on customers’ mobile devices, guiding them to the PayPal payments platform.”

That case came to an end in November after the parties reached a confidential settlement, which ultimately saw Pandora swap its blue “P” logo to one that is multi-colored (and devoid of blue), suggesting that the settlement terms required a rebrand on the part of the music streaming service.

Still yet, John Deere and Company initiated – and won – a trademark action against a South Dakota-based agricultural equipment company … over its signature colors. A federal judge in Kentucky held in October 2017 that FIMCO Incorporated cannot use “John Deere green and yellow” on its products.

In its lawsuit, Deere argued that FIMCO’s use of these colors infringed its own trademark and “diluted the value of the John Deere brand.” The judge held that John Deere’s green/yellow color combination has qualified as a “famous” trademark since as early as the late 1960’s, and that FIMCO intentionally chose green and yellow to make a connection with Deere.

Protectable or Not?

As for other brands that have been able to secure exclusive rights on their signature colors in the classes of goods/service in which they use the mark: Tiffany & Co. has federal trademark protection for its robin’s egg blue; Gap has monopolized its navy blue; Home Depot has its orange; UPS for its brown; T-Mobile for its magenta; and Post-it for its very pale yellow hue, just to name a few.

While the most recent Louboutin case is technically still pending, as it will now be sent back to the lower court for final determinations, it is accepted as good law – in a number of jurisdictions – that single color trademarks are registerable, protectable and enforceable, even within in the fashion industry, where arguments are often made as to the necessity of designers being able to freely use the entire spectrum of colors.

The ongoing war over color also serves as a reminder to brand owners that – as the Supreme Court held in the mid-1990’s in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. – color can be registered, as long as it identifies the source of the products. As such, trademark law enables brand owners to protect the distinctive features of their designs, even if the distinguishing feature is just one color, but only if they can show that consumers have come to recognize the that feature being connected to the brand. But do not be fooled. That, my friends, is a tough thing to prove.

This string of cases also serves to highlight the importance that color has in a brand’s enduring identity and its marketing strategy. In much the same way as a trademark acts as an immediate indicator of the source of a product or service for consumers, color can play an important source-identifying function. And unsurprisingly, just as many brands have been able to monetize the recognizability and appeal of their trademarks, no shortage are looking to color for the very same benefits.