image: YNAP

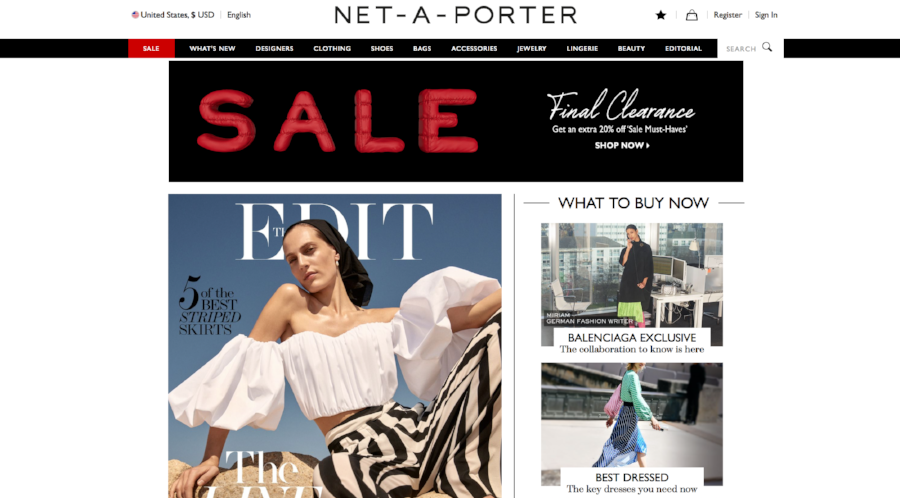

Boasting a €5.3 billion ($6.5 billion) valuation, Yoox Net-a-Porter just might be the most powerful e-commerce fashion destination in the world. Its selection, complete with routine collaborations, is unmatched. Its technological prowess – as bolstered by the YOOX NET-A-PORTER GROUP Tech Hub – is impressive. Its packaging is an Instagram dream. The website, itself, is, of course, technologically advanced, ensuring that in the age of the frequent data breach, your information is secure. But there is more to the success of YNAP than this combination of elements.

The layout of its websites matter, as do the colors of the text announcing the designers it offers, and the font of its name and the different product categories on Net-a-Porter, Mr. Porter, Yoox, etc. They matter more than you might think, according to researchers Derrick Neufeld and Mahdi Roghanizad, who recently took on the question of “How Customers Decide Whether to Buy from Your Website?”

Neufeld and Roghanizad found that “trust is essential to forming an intention to purchase.” How is such trust built, you ask? Well, according to the duo’s new study there are “hard” factors, such as privacy and security policies, but there are also other elements at play, including “font styles and colors.”

As Neufeld and Roghanizad state in connection with their study – which called on 245 individuals to visit the website of a genuine 17-year-old Australian bookstore that was unfamiliar to them, and then to make some purchase decisions – “‘Simple’ changes (such as page layouts and choices of fonts, images, and colors) may be far more critical to associative trust-formation processes than we previously understood.”

“Our findings suggest that what seem like merely aesthetic design choices may actually be the way your customers learn to trust you (or don’t),” they state. “And that will influence whether they decide to make a purchase.”

If the look and feel of a publication’s or brand’s website matters so much, it becomes a key selling point and one that entities would endeavor to protect – legally – to ensure that others are not profiting from the appearance of their site and its trust-building elements. And from this follows the questions: Are websites protectable and if so, how?

The good news for giants like YNAP (and smaller entities, as well) is that websites are, in fact, protectable by law – in more ways than one.

Copyright Law

Copyright law tends to be the first forms of protection to come to mind for most people when they think of protecting creative elements from copycats. The U.S. Copyright Office spoke specifically to the protectability of websites not too long ago, saying that while “the Copyright Act does not explicitly recognize websites as a type of copyrightable subject matter, you may be able to [protect] a website or a specific web page [as a whole as a compilation or collective work, as opposed to protecting the individual elements on the page] if it satisfies certain statutory requirements.”

For instance, the Copyright Office says that in order to be protectable, a website must contain “a sufficient amount of creative expression in the selection, coordination, or arrangement of the content appearing on the individual web pages or the website as a whole.”

While copyright law will not provide protection for “the general layout or format of a web page,” given that the level of originality/creativity required in order for a work to be protectable by copyright law is notoriously low, the protectability of “specific elements” that are part of a whole might not prove extraordinarily difficult.

Design Patent & Trademark/Trade Dress Law

Neufeld and Roghanizad’s study places significance on the fonts used on websites, which fall somewhat neatly within the realm of trademark. While trademark law will not protect the underlying design of a font in general, it will cover actual use of a font, such as Disney’s famous script in its various logos and word marks. (Note: Design patents may also cover typeface designs).

More importantly though, is trade dress law, a type of trademark law that protects the design and shape of a product itself. Trade dress protection, as some courts have held (such as the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in Ingrid & Isabel, Inc. v. Baby Be Mine, LLC), does, in fact, extend to the “look and feel” of a website.

In the Ingrid & Isabel v. Baby Be Mine case – which centered on whether you are legally permitted to copy the general appearance of a competitor’s website if you do not directly copy elements protected by copyright and trademark, such as wording and logos – the court held that “the look and feel of a web site can constitute trade dress protected by the Lanham Act [the federal law that protects trademarks.]”

In short: The design of a company’s website cannot be legally copied if consumers have come to associate that design with the company at issue (i.e., the design has secondary meaning) and that the elements at issue, such as the colors, font, etc., are not inherently useful in nature. The court in Ingrid & Isabel said that various elements, such as the “feminine script” and the use of “pastel pink-orange hues” are not functional and thereby, are protectable.

And finally, in order to be protected against copying, the copying at issue must result in a good chance that consumers will be confused about the source of the allegedly copied website.

The good news about copyright and trademark/trade dress protection is that registration is not required. Copyright protection exists as soon as you create the original work, such as the original website design. As for trademark/trade dress rights, those begin once you begin using the logos or designs at issue, meaning that if you have a protectable logo or website trade dress that you are already using, you are amassing rights as we speak and making it harder for others to legally copy them.