In 2001, just as peer-to-peer music sharing platform Napster was being shut down following a landmark legal win on behalf of the Recording Industry Association of America, version 1.0 of iTunes was being released for the first time (just a few months before the inaugural Apple stores would open their doors in Virginia and Southern California under the watch of Steve Jobs), and as Wikipedia – not the first-ever online encyclopedia, but certainly the most heavily- and frequently-trafficked – was first finding its footing, Larry Lessig was in the process of founding something headline-making of his own, even if he did not know it at the time.

A few years before any of those major tech-centric milestones, though, Sonny Bono was garnering attention of his own, albeit a long way from Silicon Valley. The singer-tuned-Congressional representative had introduced a bill to the House of Representatives. Entitled, the Copyright Term Extension Act (“CTEA”), the proposed legislation was something of a personal quest for Bono, who embarked on a career in politics after achieving world-wide fame as half of the Sonny and Cher music duo, alongside then-wife Cher.

If enacted, the CTEA would enable copyright holders, including song writers, to extend the duration of the exclusive rights afforded to them by the U.S. Copyright Act, including the right to recreate, display, and perform their original works, as well as the right to create similar works based on those original works.

The CTEA bill – a Senate version of which ultimately passed and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton in October 1998 – would extend the length of federal copyright protection beyond the time frames set out in the Copyright Act of 1976. Duration leapt from – generally – the life of the author plus 50 years to the life of the author plus 70 years. This meant that copyright holders, such as the writers of song lyrics, (and their estates) now had the exclusive right to control his/her work for longer than ever before.

Meanwhile, beyond the hallowed halls of the nation’s legislature, Larry Lessig was between tenures at Harvard and Stanford law schools. The lawyer and professor would soon become not so removed from the makings of the CTEA. Thanks to his specialty in constitutional law, intellectual property, and cyberspace, Lessig had been called upon to take on a case. To be exact, Lessig was enlisted as lead counsel in Eldred v. Ashcroft, a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of that very bill.

I Fought the Law (And the Law Won)

For Eric Eldred, the passage of the CTEA was personal, as well. Reflecting on the case, some years later, Lessig recalled how it all began: Mr. Eldred, a computer programmer and doting father, wanted to make the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne attractive to his digitally-connected young daughters – before the existence of e-books, iPads, and Kindles. To do so, he “put Hawthorne on the web. An electronic version with links to pictures and explanatory text, [which] Eldred thought, would make this 19th-century work come alive.”

From there, Eldred “went on to build a library of public-domain works” – i.e., creative works for which copyright protection, including the right to reproduce and display, had expired – “by scanning these works and making them available [online] for free.”

“In 1998, Robert Frost’s poetry collection, New Hampshire, was slated to pass into the public domain,” Lessig explained. Eldred knew this. In light of the impending change in legal status for the Frost poetry, Eldred “wanted to post the collection [of poems] in his free public library. But Congress got in the way.” More specifically, Congress got in the way with the CTEA, which represented the 11th time in just four decades that the legislative body had extended the duration of protection for existing copyrights.

Thanks to the newly-enacted law, Eldred could not legally add any works published after 1923 to his collection until 2019, since, “under this new law,” says Lessig, “no copyright-protected work would pass into the public domain until that year (and not even then, if Congress extended the term again).”

If Eldred had uploaded the poems to his makeshift digital library, he would have been running afoul of copyright law.

It was here that Lessig entered into the picture. Eldred had decided it was time to challenge the law.

In the eyes of Lessig and Eldred, the passage of the CTEA was a direct violation of the Constitution of the United States. In Lessig’s view, in addition to giving rise to copyright protections in the U.S., the Constitution simultaneously places a limit on the duration of copyright law. This is evident in the language of the Constitution’s “Copyright Clause.” Article I Section 8 Clause 8 grants Congress the power to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries – as a way to ensure that copyright holders do not too heavily influence the development and distribution of our culture.”

“Limited times” is the critical element here.

With such language in mind, Eldred enlisted the help of Lessig, who had already determined that, as he would state on the 12th anniversary of the launch of the first Creative Commons license suite, “The internet was changing the way people share, and changing what it meant to be a creator. But copyright law hadn’t caught up. The Net was making sharing easy; the law was making it hard.”

So, the two men joined together in furtherance of what Lessig has called “Eldred’s crusade to save the public domain,” and a ground-breaking legal challenge was born, one that would ultimately go before America’s highest court.

Eldred’s complaint – which named U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft as the defendant, as federal law requires that when a federal law is alleged to be unconstitutional, the Attorney General must be served with a copy of the complaint and must be entitled to be heard – was filed in January 1999 in federal district court in Washington, D.C. With the help of Lessig, Eldred was challenging the constitutionality of the CTEA.

“We made two central claims,” Lessig recalls: 1) “extending existing terms violated the Constitution’s ‘limited Times’ requirement;” and 2) “extending terms by another 20 years violated the First Amendment” in that the law served as a restriction on freedom of speech.

Both of those claims would fall short before the lower court, the court of appeals, and ultimately, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court, which was, of course, lobbied significantly by major media companies (including Walt Disney Co., the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry Association of America), congressmen, and various copyright holders, all of which submitted in amicus briefs in opposition to Eldred’s case and in favor of the extension of the duration of copyright protection.

The Birth of Creative Commons

The case, itself, ended in an unfavorable ruling for Lessig and Eldred, but not all was lost. They made sure of it.

While the case was still underway, Eldred became skeptical as to his and Lessig’s ability to secure a victorious outcome. So, he approached Lessig with a plan. “He wanted to make sure that out of the litigation wouldn’t just come a losing case at the Supreme Court,” Lessig told Governance Across Borders in 2012. He wanted “something that would be a more fundamental foundation to support what we’ve come to call Free Culture.”

Lessig was confident that change would not be achieved in the hallowed halls of Congress. Instead, he decided that they would have “to build the movement of understanding in people … It had to come from the bottom up.” And from there, Creative Commons was born under the watch of Lessig, Eldred, and Hal Abelson, the latter of whom is a professor of computer science and engineering at MIT.

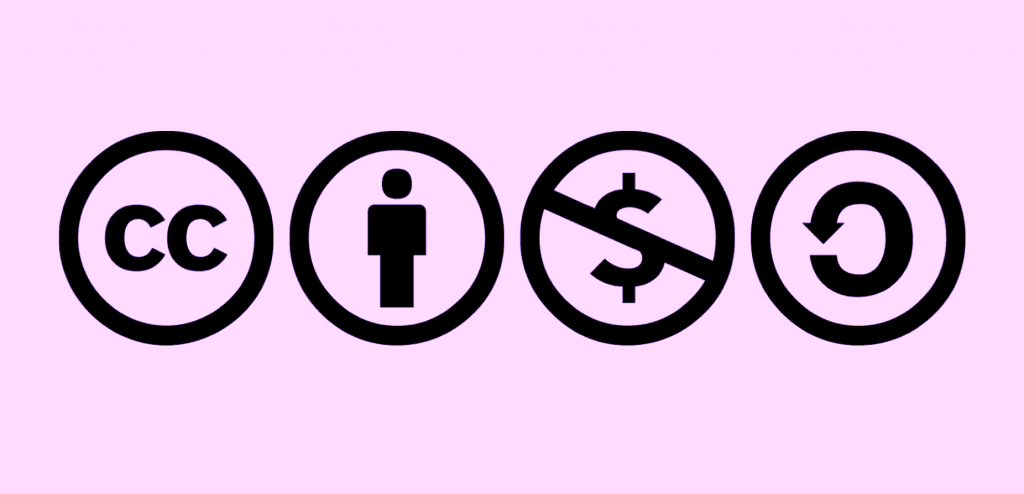

18 years later, Mountain View, California-based Creative Commons is known for its in-house developed copyright-licenses, among other “legal and technical tools that also facilitate sharing and discovery of creative works.” Free sets of tools that enable creators to communicate to the public the specific rights they reserve (i.e., that they claim exclusive control over, such as the right to make commercial use of the work) and which they have opted to waive and make legally available for public use, the Creative Commons licenses fit into the non-profit organization’s larger aim to help build a robust public domain.

Instead of eschewing copyright protections altogether, something Lessig and his Creative Commons compatriots have certainly been accused of, Creative Commons licenses recognize “the need for evolution in copyright law” in light of how the internet has changed “the way people share, and changed what it means to be a creator.” With that in mind, in Creative Commons’ view, creatives can – and should – have access to alternatives to the “all rights reserved” protections afforded by copyright law in the U.S.

In other words, creatives, with the help of standardized Creative Commons terms, can license and/or distribute their copyright-protected works in ways that are more dynamic than the U.S. Copyright Act sets forth.

Just one example cited by Creative Commons of a type of use that traditionally falls outside of the bounds of non-infringing use of a creative work is the option for a photographer to enable others – by way of language in a specific CC license – to have access to a lower-resolution photograph, but only distribute high-resolution copies to people who have paid for access. This enabled to public to gain access to the work at issue, while enabling the copyright holder to still maintain his/her ultimate bundle of copyright-afforded rights, including the exclusive right to monetize the work.

“One billion licensed works later, I think we were right,” Lessig said in late 2014, referring to the impact of Creative Commons, an innovation he describes as a system of licenses “that creators and other rights holders can use to “reserve rights” for themselves, while offering certain usage rights to the public,” i.e., the “commons,” in furtherance of the greater goal of “helping to realize the full potential of the internet.”

And creatives across the globe have been receptive. “I certainly didn’t know that [Creative Commons] licenses would catalyze a global community in almost 80 countries,” Lessig revealed on the 12th anniversary of the founding of Creative Commons. Beyond “governments and foundations” that have taken the organization’s “values and embedded them in official policies,” many artists, including musicians and groups, like Nine Inch Nails, Beastie Boys, Curt Smith, David Byrne, Radiohead, Yunyu, Kristin Hersh, and Snoop Dogg, have used Creative Commons licenses to share their works with the public.

As for how Lessig has seen the landscape change, he told the Wikimedia foundation, “In the sense of taking media content and remixing it, we’re just beginning to see a lot of that. But that’s because the technology is just beginning to penetrate.”

Still, he says, “It’s going to take time before people feel comfortable with that.”